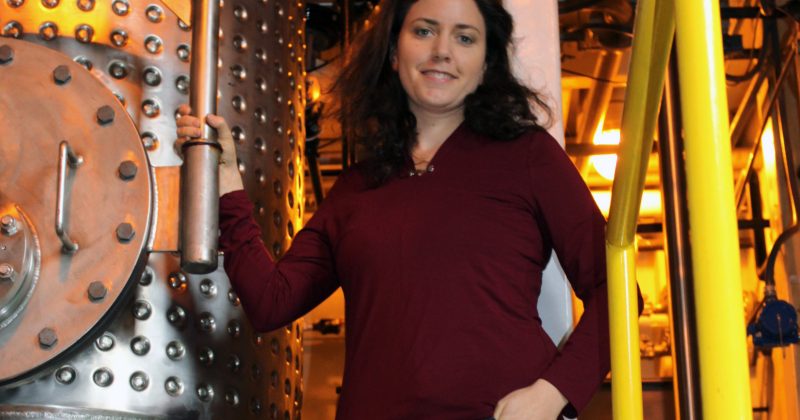

Malinda Maynor Lowery's students take at least one trip to Robeson County to do a service project, talk with Lumbee tribal members and tour historical sites. (photo by Dan Sears)

Click on the links at the bottom of this story for more features on creative teaching and learning in the College.

The past and the present are interwoven in the classroom of Malinda Maynor Lowery, associate professor of history. Lowery is intent on conveying to her students the message that history matters because it helps teach people how to live in the present.

“The root of this kind of teaching is that history fundamentally teaches us how to think about the cultural assumptions we have as human beings,” she said. “Those assumptions inform our actions, the ways we treat other people and the decisions that we make today.”

This spring, students in Lowery’s “Native American Tribal Studies: Lumbee History” class are exploring those cultural assumptions, as well as the history and stories of the Lumbee and Tuscarora people in their Robeson County homeland. A Lumbee Indian with a special interest in Native American history, Lowery said it is not enough to read texts; it’s crucial that her students also interact with the Lumbee community.

“Talking with people about their past brings history into a living, breathing conversation that changes students’ attitudes about history and about native people as well,” said Lowery.

She says that her experience as a Faculty Engaged Scholar through the Carolina Center for Public Service helps her articulate to her students the importance of engaged scholarship.

“This method of research is a two-way street,” said Lowery. “It means going to the people whose ancestors you are studying and saying to them, ‘I want to work with you to answer a question about your ancestors that you feel is valuable. And I can share knowledge and resources with you that you may not have access to.’”

Lowery’s students take at least one field trip to Robeson County to do a service project, talk with tribal members and tour historical sites.

“It’s important to get a real feel for Lumbee people: how they talk and what they talk about,” she said. “And students learn the role that the land plays in forming our community and our history and get to understand the idea of place as an actor in history.”

Another major focus of the class is original research conducted by the students.

“One of the benefits and drawbacks of teaching Lumbee history is that there isn’t a lot of secondary literature about it,” said Lowery. “This leaves students with little direction by other scholars. But on the other hand, it opens a lot of exciting opportunities for undergraduates to do research that is self-directed.”

Lowery says that the efforts of students conducting research about Lumbees in concert with members of the tribe enable conversations and partnerships.

“Engaged scholarship is about producing knowledge in collaboration with a community that is affected by that knowledge,” she said. “It’s exciting to watch my students get excited about doing this.”

Lowery is also energized about using her own research to benefit the Lumbee community.

“It would be silly to do research about Lumbees without involving the Lumbee people,” she said. “Although I grew up in Durham and live in Durham now, we had strong and constant connections to Robeson County when I was a child. I have lived there off and on for the last 10 years and have my own questions about our past.”

Those questions deeply inform her work. Her first book, Lumbee Indians in the Jim Crow South: Race, Identity, and the Making of a Nation (2010), examines how the Lumbee people challenged the boundaries of Indian, Southern and American identities. The book she is currently working on — with the working title The Lumbee Indians: An American Struggle — results from conversations with the community that she had after the publication of her first book.

“Many Lumbee and Tuscarora people were glad that I had written about them but asked whether I could make the narrative more understandable. I wrote my first book to speak to other academics, but this book is designed to speak to my own people, who the book is about,” she said.

Learn more about Faculty Engaged Scholars at ccps.unc.edu/faculty-engaged-scholars.

[Story by Michele Lynn]

Read more stories on creative teaching and learning, part of the package “Learning 2.0″:

Intro to entrepreneurship (super course)

Interactive psychology instruction

Physics inside out

When literature and history leap off the page

Champion of undergraduate research

Published in the Spring 2013 issue | Features

Read More

Champion of Undergraduate Research: Pat Pukkila has transformed the Carolina experience

Biology professor Pat Pukkila has infused undergraduate research into the…

Liberal Arts Leader: Rachel Burton ’96, Women’s Studies

Rachel Burton didn’t just land a great job, she invented…

A Liberal Arts Rhodes: The road for senior Rachel Myrick leads to Oxford

Senior Rachel Myrick will head to Oxford University on a…