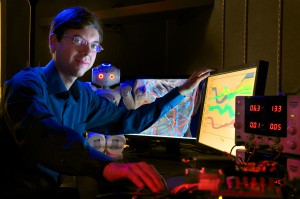

UNC music professor Lee Weisert records water sounds at a rock quarry pond in Caswell County, N.C. (photo by Steve Exum)

When Lee Weisert first heard the chords in “The Rite of Spring” as a high school student, the hairs on the back of his neck stood up.

“There was a physical quality to the music that created a direct engagement with sounds I had never heard before,” says Weisert, an assistant professor in the department of music. Inspired by Stravinsky’s opus and influenced by John Cage’s pioneering work in seeking out new models for musical composition, Weisert embarked on a path toward music composition.

Weisert composes three types of music. “I create acoustic chamber pieces for various combinations of cello, piano and other traditional instruments,” he says. “There are purely electronic pieces that I write for the computer, usually for a fixed multichannel playback. And then there are sound installations on which I collaborate with a colleague, Jonathon Kirk, a professor at North Central College in Illinois.”

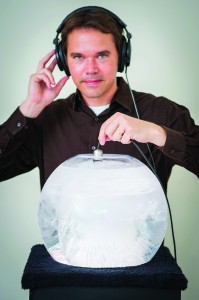

These installations explore the sounds created by water in its liquid and solid states. Last year, Weisert and Kirk created “Cryoacoustic Orb,” which featured multiple illuminated acrylic orbs filled with slowly melting ice. Hydrophones (underwater microphones), frozen inside the ice, amplified the sounds of the melting process. Those sounds were then electronically processed and broadcast through the gallery space, creating a soundscape that evolved over the course of several hours.

“I’m interested in the acoustic ecology movement which is a cross between the natural sciences and music composition,” says Weisert. “People have been recording interesting sounds in the environment from different areas of the world with some of the most beautiful recordings being the ice floes cracking and moving in the Arctic.” Weisert says that this work was a trigger for his project as were the hydrophones he and Kirk purchased for their 2008 collaboration, “The Argus Project.”

That site-specific sound installation explored the sound sources from beneath the surface of a natural pond. “The pond supplied all the sonic material, like the gurglings and bubblings and the occasional fish trying to eat the microphones,” says Weisert. “All of those sounds were captured by the hydrophones. In addition, we had sensors that picked up changes in the environment, such as temperature and light, which was translated into data that the computer altered into sounds.” Weisert says that the pond becomes both the instrument and the performer. He plans to stage this piece in Chapel Hill in 2013.

“I am intrigued by the sonic accessibility to a place that you can’t access in a normal situation without all of this technology,” says Weisert. “That direct simple discovery of this sound world is exciting.” Weisert says that the sound installations inspire his other musical compositions.

“I, along with other composers of instrumental and computer music, am always looking for new things to base my compositions on outside of the traditional forms, ideas or gestures,” says Weisert. “These sound installations offer textures that I would never think of myself.”

Weisert says that he can take the sounds he discovers and reshape them for a string quartet or another more traditional piece of music. “Some of the sound worlds, behaviors and shapes that came out of the installation are definitely creeping in to the electronic part of a piece I am now writing for saxophone and electronics,” he says.

Watch a video of “Cryoacoustic Orb.”

[Story by Michele Lynn, fall 2012 Carolina Arts & Sciences magazine]

Published in the Fall 2012 issue | Features

Read More

Precious Resource: Scientist saves lives through clean water

Greg Allgood (B.S. ’81, M.S.P.H. ’83), a Procter & Gamble scientist,…

The Future of the Outer Banks: Climate change’s effect on N.C.’s barrier islands

Laura Moore uses historical maps, geologic data and computational modeling…