UNC friends are among the conservationists working to restore the folk art of beloved N.C. folk artist Vollis Simpson. (photo by Mary Lide Parker)

Past tobacco fields down a winding country road, the drive is reminiscent of many of North Carolina’s rural landscapes. But around the bend, at the intersection of Willing Worker and Wiggins Mill roads in Lucama, they start to rise up out of the field — massive, 50 and 60-foot-tall spinning sculptures that look like pinwheels on steroids.

You feel like you’ve entered another world — a larger-than-life game board, a Santa’s tree-top workshop for giants.

For more than 25 years, both locals and visitors from near and far have traveled to the “whirligig farm” of 93-year-old folk artist Vollis Simpson, a former machine repair shop owner and World War II veteran.

He made his first windmill for utilitarian purposes when he used a junked B-29 bomber to power a large washing machine on the South Pacific island of Saipan during the war. He lost his best buddy there, 18 years old, on their third day there.

After returning from the war, Simpson and his friends opened a machinery repair shop, and following in his father’s footsteps, a house-moving business. But when retirement time rolled around in 1985, Simpson didn’t want to sit by idly twiddling his thumbs. He started using junk he had collected — HVAC fans, bicycle parts, ceiling fans, stovepipes, textile mill rollers, highway road signs and the like — to create intricate whirligigs in the field across from his shop. Airplanes, animals and bicycles are often themes in his work.

A UNC connection

Over the years, Mother Nature has not been kind to the whirligigs, and Simpson is not able to climb and repair them like he used to do. That’s where UNC folks are stepping in through a unique public-private partnership that could be an economic, artistic boom for the area where tobacco was once king. They are dismantling about 30 of the sculptures — some weighing several tons — and restoring them to their former glory in an old warehouse in downtownWilson. Simpson’s now famous works will be moved to a two-acre park nearby that will offer an amphitheatre, a performance stage, a water feature, park benches and more. Organizers envision a site for concerts, reunions, weddings, festivals, a farmer’s market. The Vollis Simpson Whirligig Park is scheduled to open in November 2013.

Wilson native Betty McCain (music ’52), former long-time secretary of the N.C. Department of Cultural Resources, is a champion of the project. She believes it will draw tourists off I-95 into downtown, which already boasts an art gallery, a science museum and a revitalized community theater.

“We’ve really had to diversify because we were the world’s largest Brightleaf tobacco market,” she said on a visit to the restoration headquarters. “There’s a great deal of tobacco still being done on contract, but the warehouse system is over. The people in the tobacco industry worked all over the world, and they know what this whirligig park will mean.”

When project manager Jenny Moore (art education ’72, art history ’86) first heard about the conservation venture, she immediately called Henry Walston (business ’70), head of the project committee, and told him she wanted to return home to be involved. The effort has received grants from significant funders, including the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA), the Kresge Foundation, the Educational Foundation of America and the N.C. Arts Council. Retired engineers, welders and master machinists are helping with the project, and a new grant from the N.C. Rural Center will help support job training for under-privileged youth.

“There’s a real focus in the country, from the NEA and private foundations, on economic development in relation to the arts,” said Moore, who is among many with UNC ties involved in the endeavor, including historian Bill Ferris of UNC’s Center for the Study of the American South who serves as an adviser. “Most of our funding has come to this project not just as a sculpture park, but more of what it’s going to mean to the community. … When you get people coming to the park because they want to have a picnic with their kids and have fun, they are having an art experience in a public place whereas they might not have intentionally gone to a museum to see art.”

At 93, still making art

On most days, you’ll find Simpson in his repair shop early in the morning, dressed in blue jeans and wearing his U.S. veterans baseball cap, still creating colorful works of art and trying new things — but on a smaller scale. His work can be found at the American Visionary Art Museum in Baltimore, the American Folk Art Museum in New York City and the N.C. Museum of Art in Raleigh. Four whirligigs were commissioned for the 1996 Olympics in Atlanta. He has won honors ranging from the North Carolina Award (the state’s highest civilian honor) to Southern Living magazine’s “Heroes of the New South.”

“When I started this here, you never heard tell of the word art,” he said, as a black cat meowed at his feet. He has mixed feelings about the sculptures being moved, but knows that the timing is right. The work can be dangerous — he caught on fire in a serious welding accident several years ago– but he said “everything I’ve ever done is dangerous.”

“I’m not able to climb no more and I reckon it’s a good thing. I really hate to see them go, though,” he said, pausing. Then with a big grin he added, “But we’ve all got to go.”

Art can change the world

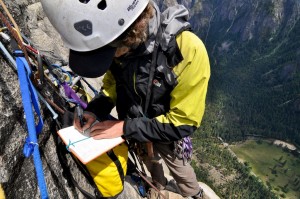

Jeff Currie, who is pursuing his master’s in folklore at UNC, is overseeing surface conservation and documentation of the initiative. Simpson’s life informs his work, Currie said.

“He is a great engineer and mechanic and a very good artist, but he’s also really, really patient,” Currie said. “Some of the things he does, you feel the patience in them. Doing one thing — [like cutting and drilling tiny pieces of reflectors] — 2,000 times. He’s among that generation that has to work.”

Like many of her project colleagues, working with Simpson has been a labor of love, said Laura Bickford (art history and folklore ’10), who is an intern with the project and will be doing a master’s thesis at The Art Institute of Chicago on Simpson’s work.

“Vollis’ work to me is so honest,” Bickford said. “And to see it here, now being restored by people from this same place, and seeing how it can become a new source of pride for the town is so amazing, and it’s what art should be doing everywhere. That is the point of art. ”

“Art can change the world. It can make a difference.”

[Story by Kim Weaver Spurr ’88, multimedia feature by Mary Lide Parker ’10. This story is featured in the fall 2012 Carolina Arts & Sciences magazine. ]

Published in the Fall 2012 issue | The Scoop

Read More

Meet the Teacher: Jean DeSaix, biology

Jean DeSaix, a UNC biology master lecturer, understands those university…

Total Immersion: The art and science of water in our world

For more stories about water initiatives in the College, click…