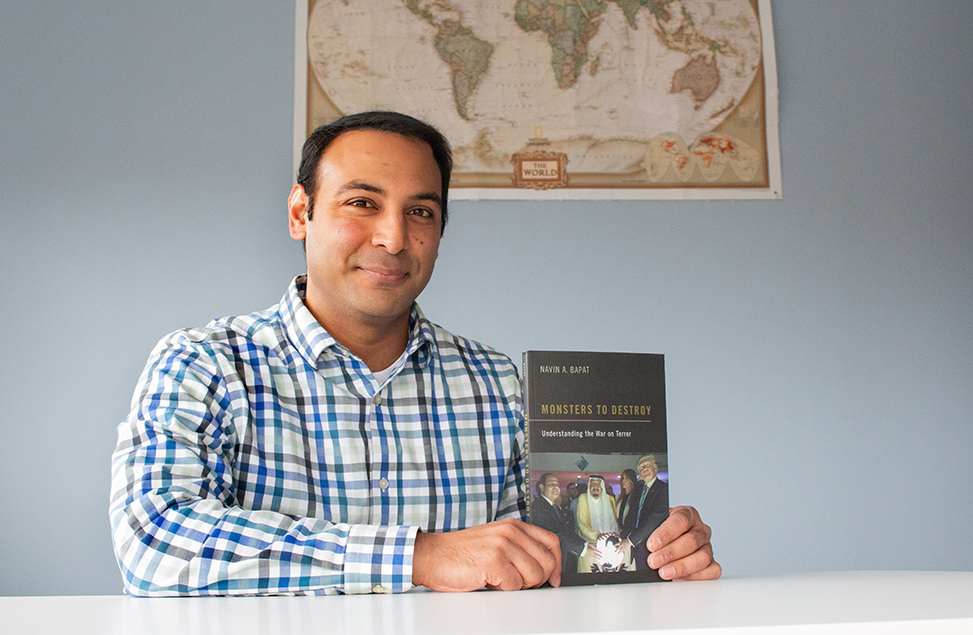

Navin Bapat fears that the recent U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan and the subsequent Taliban takeover may reverse the tenuous social and educational reforms. (photo by Kristen Chavez)

An expert on global terrorism uses a long lens to explain what happened in Afghanistan — and what might happen elsewhere.

Navin Bapat had already begun to research terrorism as a graduate student in political science when 9/11 happened. The shock of the attacks on U.S. soil made that research all the more important — and opened the door for a different perspective.

At first he viewed terrorism through the lens of his background: “My parents are from India, and they often described these individuals as irrational and religious fundamentalists. And they described terrorism as a pretty significant threat,” explained Bapat, the Dowd Professor in the Study of Peace and War and chair of the curriculum in peace, war and defense (PWAD). “But when I looked at the data, I soon realized that wasn’t correct.”

The United States was spending multi-trillion dollars to fight something that affected fewer people than were killed in automobile accidents every year, he said, so his focus shifted to understanding the other factors at play.

Historical documents showed that al-Qaida originated in Saudi Arabia, a country the United States was supporting. Because the Saudis’ internal rebels were portrayed as terrorists, presenting U.S. support as an effort to help the country fight terrorism made the issue cleaner politically and easier for the American public to support, he said.

The level of financial support and willingness to sacrifice American lives in a war on terrorism was disproportionate to the problem, Bapat said, which led him to believe the broader issue was U.S. control over global energy markets, and in turn, global trade. As he explained in his 2019 book Monsters to Destroy: Understanding the War on Terror, Bapat believes the U.S. government offered military protection to various countries because they were critical in extracting, selling and transporting oil and natural gas.

While the idea was to provide assistance until the countries could manage terrorism on their own, it actually created a disincentive for the leaders to take action, he said. Former Afghan President Hamid Karzai is a prime example.

“He believed the United States would support him forever, so he never had an incentive to make Afghanistan a secure state,” Bapat said.

In its 20 years in Afghanistan, the United States did score some victories in the war on terror, but Bapat fears that the recent U.S. withdrawal and Taliban takeover may reverse the tenuous social and educational reforms.

His current research focuses on the effectiveness of economic sanctions. As they increase the price of trade between countries, sanctions create inefficiencies in trade that make it untenable.

“The most effective sanctions are those that are threatened but aren’t actually implemented. It’s the threat that affects a government’s willingness to change its behavior,” Bapat said.

This semester he is teaching a graduate course on bargaining theory and negotiation, and next spring he’ll teach the undergraduate course on terrorism he began teaching even before he came to Carolina in 2007.

PWAD students go on to a variety of careers — from intelligence or defense work to law and journalism, among many other fields. “We teach them to analyze a situation and predict future outcomes. We also teach general leadership skills, how to examine what’s been done in the past, how mistakes are made and how to deal with uncertainty, even with all the available information,” Bapat said.

The curriculum also is expanding its focus on human security issues.

“When we talk about peace, we think about the absence of war between states, but we don’t always talk about what happens within those states,” he explained. “Some states have repressed policies for the people who live there, so it really isn’t peace for them.”

Learn more in an interview with Bapat at college.unc.edu/2021/08/bapat.

By Patty Courtright (B.A. ’75, M.A. ’83)

Published in the Fall 2021 issue | Tar Heels Up Close

Read More

‘Undergraduate research changed my life’

Troy Blackburn (B.A. exercise and sport science ’98, Ph.D. human…

New gift marks the importance of support for clinical psychology graduate students

As the No. 2 ranked clinical psychology graduate program (U.S….