Oswaldo Estrada is interviewing Latino immigrants in North Carolina about their experience for a collection of stories. (photo by Donn Young)

The Institute for the Arts and Humanities’ Faculty Fellowship Program provides semester-long leaves for faculty to pursue research and creative work. In 2019, the institute announced it would award additional fellowships dedicated to faculty projects focusing on race, reckoning and memory.

The first two faculty to receive IAH Race, Memory, and Reckoning Initiative funding are Oswaldo Estrada, professor of romance studies, for a hybrid book of stories about the Latino immigrant experience in North Carolina, and John Sweet, associate professor of history, to explore how the built environment of Chapel Hill was shaped by Jim Crow. The initiative will fund two more fellowships next year and again in 2022-2023.

A hybrid space

In 2019, Oswaldo Estrada was teaching a first-year seminar on immigrants crossing the U.S.-Mexico border when he had a revelation: The stories that Latino students at UNC had shared with him about their immigrant experience were every bit as compelling as the ones he was teaching. It was time to gather these stories, and the stories of other Latino migrants who had made their way to North Carolina.

Estrada had the perfect background to embark on such a project. Although he was born in the United States and is a U.S. citizen, he spent most of childhood in his native Peru, and Spanish is his first language. His family returned to the States when he was 14, and he has lived like an immigrant ever since, having to learn English and adjusting to American culture.

“When you cross the border, it changes your life deeply. It’s not just a physical change. Mentally and forever, it changes you. There’s a ‘before’ and ‘after’ you come to the United States, and you learn how to inhabit an intermediate zone, a hybrid space where you don’t always feel at home,” he said.

He is working on a book of short stories on Latinos in North Carolina, that he hopes to complete during his research leave under the IAH fellowship this semester. Although the stories are based on real accounts, they have been fictionalized.

“Fiction allows me the liberty to gather from several stories at once,” said Estrada, the author and editor of several books of literary and cultural criticism as well as works of fiction that have received the International Latino Book Award. “It also lets me protect the identities of those who have trusted me with their stories.”

In one of the pieces, “A Sip of Benadryl,” a young woman recounts a story her mother told her of being smuggled into the country as a toddler, and how the experience has shaped her life today. Estrada said the story, based on several conversations with his undergraduate students, captures what it’s like “to always be afraid. Because you see a cop down the road and you don’t have the papers to be here. And it’s not your fault — you came when you were 2 years old.”

In addition to interviewing students, Estrada is gathering stories from others in the community —including Lenoir Hall food staff, area nannies, day laborers and workers at the Carrboro Farmers Market.

North Carolina has the fastest-growing Latino population in the United States; growing by 394% since 2000. They are “the workers who are keeping our economy going, cleaning our office buildings, the day workers. There are so many of them, but we don’t always see them and they remain invisible,” he said.

“We think we are so far removed from the Mexican border. But this is a North Carolina story.”

Seeing segregation

John Sweet’s specialty is Early American history, but a few years ago he developed a first-year seminar, “Seeing History in Everyday Places,” that explored Chapel Hill’s physical development over the 20th century.

“I designed this class to introduce students to a way of seeing the world around them, in which they see manmade features like buildings and roads and transportation networks as products of history,” he said, noting, for example, that many of North Carolina’s major highway routes have their origins in Native American trading paths.

He also wanted to show students the enduring legacies of slavery and racial segregation. “It was a story I thought I knew,” he wrote when applying for the IAH fellowship. “But my students and I were astonished at what we uncovered.”

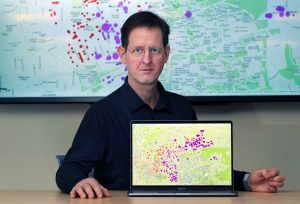

With assistance from University Libraries’ digital specialists, Sweet and his students used GIS technology to create a map that layered data from the 1930 U.S. Census and a detailed 1932 fire insurance map on top of current town property maps. The students then combined the geographic and quantitative data with recordings from the Southern Oral History Program archives, 1930s film footage and other sources to provide more context. They examined property values, migration patterns, employment and education records.

The results showed just how starkly the geographic color line cut through Chapel Hill.

The power of GIS mapping is that it reveals patterns that would normally not be apparent, said Sweet. For example, on the east side of Chapel Hill, which was predominately white and populated by faculty and other employees of the University, the 1930s census data show that people moved here from all over the country. However, in Black neighborhoods, residents came primarily from elsewhere in North Carolina or parts further south.

“For Black Americans in the early 20th century, migration typically meant moving northward,” Sweet said. “Chapel Hill was a place of opportunity for a wide range of white Americans but was not a place of opportunity for Black people from most of the country.”

Sweet and his students also found that town directories published at the time — which supposedly listed all inhabitants of Chapel Hill —listed only white residents, a sobering reminder of how racial segregation involved not just separation and hierarchy but also symbolic erasure.

Another enduring legacy is the way public school district boundaries were drawn — starting with the first graded school district in 1915, which carefully excluded Black neighborhoods. These neighborhoods had to fund their own schools until much later.

“Flash forward 100 years and Northside Elementary School still has a convoluted district that includes almost all of the historically Black areas we’ve been looking at,” Sweet said. “And it has consistently been the worst-performing school in the Chapel Hill-Carrboro district, according to state rankings. That educational inequality has continued to the present, within a half-mile of a great university.”

Sweet will be teaching the first-year seminar again in fall 2021 and plans to continue the research for his project, “Seeing Segregation in Everyday Places,” perhaps mapping Carrboro, or delving more deeply into the area’s historic Black business districts. His hope is to produce an essay or other work using the physical landscape of Chapel Hill to create a window into the lived legacies of Jim Crow and Black equality struggles.

By Geneva Collins

Published in the Spring 2021 issue | Tar Heels Up Close

Read More

Carolina students reflect on a year of COVID-19

After a year of remote learning and being away from…

Read more books: Additional offerings by College faculty and alumni

I Am a Man: Photographs of the Civil Rights Movement,…