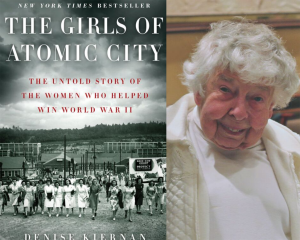

Virginia Spivey Coleman, 96, has been a member of the Smoky Mountains Hiking Club for over 50 years. (photo courtesy of Virginia Spivey Coleman)

UNC alumna was among “The Girls of Atomic City” who worked on the development of the first atomic bomb.

Virginia Spivey Coleman (chemistry ’44) remembers vividly the day a recruiter from Oak Ridge National Laboratory in Tennessee came to UNC-Chapel Hill to tell her about an exciting opportunity.

“She described Oak Ridge as being this 90-square-mile reservation with free buses and movies and everything staying open 24 hours a day,” said Coleman, now 96. “I took a train for the first time for an interview [in December 1943], and on the way back it snowed and the train was six hours late arriving. It was jammed with soldiers on leave for Christmas.”

Coleman ended up taking the job, arriving at what was called “the bullpen” for about six weeks while she waited for a mix-up in her clearance to go through. Her first position was in human resources. She later switched to the lab of Clarence Larson, a senior chemist in the Y-12 plant, where she worked on analyzing how thoroughly the enriched uranium was chlorinated.

She had no idea she was working for the U.S. atomic weapons program on developing the first atomic bomb — which would eventually be dropped on Hiroshima on Aug. 6, 1945.

Coleman and other female scientists were featured in the 2013 book The Girls of Atomic City: The Untold Story of the Women Who Helped Win World War II by Asheville writer Denise Kiernan.

Kiernan wrote in the introduction that because of the women of the Manhattan Project, “a new age was born that would change the world forever.”

Social life at Oak Ridge was wonderful, with “five males to every female,” Coleman said, laughing. “They had dancing on the tennis courts every Friday night and the largest pool in the United States, and a cafeteria right across from my dorm where you could get a cup of coffee and talk,” she added.

Coleman graduated with an associate’s degree from Louisburg College, a two-year residential college in her hometown of Louisburg, N.C., and transferred to Carolina as a junior. She said she “never thought about going anywhere else.” Her sister, Sophia, was already there, working on a master’s degree in chemistry. She proved to be very helpful in getting Coleman through organic chemistry classes.

Coleman worked hard at UNC, with lab every afternoon and shifts in the university’s dining hall serving tables from 6 to 9 p.m. “We got $1 and we got our dinner. I sometimes worked at the desk at the dormitory where I lived and I got paid 35 cents an hour for that.” She also played on the tennis team and remembers fondly the walks in Coker Arboretum.

After the war, Coleman stayed on at Oak Ridge for nine years, working for Dow Chemical. She met her future husband there, and they settled down and had a family.

Her career took a major shift when she decided to go back to the University of Tennessee for a master’s in social work, transitioning from what she calls “hard science to soft science.” She worked for Child and Family Services on a federally funded project to fight sexual abuse. She later helped to create Healthy Start, a program modeled after one in Hawaii that educated young mothers about preventing childhood abuse.

Coleman still lives in Oak Ridge, is in two book clubs and has been a member of the League of Women Voters and the Smoky Mountains Hiking Club for over 50 years. Despite suffering from lymphedema, she walks around the circle in her neighborhood as often as she can, using her hiking poles.

She last visited the UNC campus about 10 years ago, where she admits she was a bit lost because of all the changes.

Still, she said, “I always loved Chapel Hill.”

By Kim Weaver Spurr ’88

Published in the Fall 2019 issue | Tar Heels Up Close

Read More

New College initiatives tackle difficult topics

Under the leadership of Interim Dean Terry Rhodes, the College…