Daye has won both the American Poetry Review/Honickman First Book Prize and the Whiting Award for previous works. (photo by Beowulf Sheehan)

Haunting images, childhood memories, and both the joy and pain of growing up in the rural South fill the pages of award-winning poet Tyree Daye’s work. The teaching assistant professor of creative writing’s newest collection, Cardinal, explores themes of the Great Migration through his lens as a Black man navigating away from — and returning to — the place he calls home.

Tyree Daye has been thinking a lot lately about how complicated the idea of home is — what memories to hold on to and what to let go.

“It’s something that’s always going to be difficult,” said Daye, who grew up in Youngsville, North Carolina. Themes of substance abuse, death and racism are interwoven with images of family, childhood innocence and Southern landscape in his work. “I think it’s my duty as a writer to find those places of love that are connected to home while not ignoring the trauma. With the newest poems in Cardinal, I’m exploring this idea of traveling and trying to find a safe place to be and to live.”

Daye discusses that duality further in a Southern Futures podcast episode, “The Push and Pull of the South,” sharing, “I can’t hate a place where my grandmother’s buried.”

That sense of place, that connection to his ancestry and to his grandmother’s Gullah/Geechee culture, also opens the 2017 poetry collection, River Hymns.

He begins “Dirt Cakes” this way:

My Grandmother’s body

lives under an ash tree

on an old church ground, her spirit

can be seen making

a maple tree’s shadow jealous.

Daye said “Dirt Cakes” is still his favorite poem in that inaugural collection, which won the American Poetry Review/Honickman First Book Prize. He is only the second African American poet to win the prize since it was first awarded in 1998.

“It feels like an opener to me. If it’s a movie, it’s a wide shot over the town, there in the graveyard,” he said. “Everything starts with my grandmother. It feels high up.”

Poet Gabrielle Calvocoressi, associate professor of English and comparative literature and Walker Percy Fellow at UNC, wrote in the introduction to River Hymns that through Daye’s poetry she was able to see landscapes that were very familiar and personal to her in a new way.

“This seems to me to be important now more than ever: the ability of the poet to show us a world we thought we knew and then expand our understanding,” she said.

Becoming a poet

When he was in high school, his mother gave him a copy of The Collected Poems of Langston Hughes. Daye said he came from a family of storytellers, but it wasn’t until his junior year at NC State University that he became serious about writing poetry.

As an undergraduate creative writing major, he discovered the poems of Lucille Clifton and Etheridge Knight. A quote from Clifton is on the front page of his website: “In the bigger scheme of things the universe is not asking us to do something, the universe is asking us to be something. And that’s a whole different thing.”

That quote still speaks to him today, both as a poet and an educator.

Daye said after he received his bachelor’s degree in English, he thought about moving to New York City to pursue a master’s degree. Now, he laughs at that, saying, “I would have missed the trees in North Carolina.” He went on to receive an MFA from NC State with a concentration in poetry.

“I think about it now — what would have happened to my poems? I was always trained to write about what you know and to investigate what you think you know. I don’t think I could have done that anywhere else,” he said. “I was trying to run away from home instead of examining my home.”

In 2019, while teaching at both Louisburg College (in Louisburg, North Carolina) and UNC-Chapel Hill, Daye got a call that he had won a $50,000 Whiting Award, one of poetry’s most prestigious prizes given to emerging writers.

The Whiting Committee called Daye’s poems “haunted and haunting; they make new a familiar human loss and longing.”

Teaching young poets

This fall, Daye is teaching two introduction to poetry courses as well as English 105, the composition and rhetoric course required of all undergraduate first-year students.

He said he enjoys teaching young students because he also learns something new each time. Helping them to dissect their poetry line by line and hone their craft often opens up something in his own work. Most of all, whether they go on to become poets or not, Daye wants to teach students how to be vulnerable.

He encourages them to read their poems out loud, to read them backward and forward.

“Have they revealed something about themselves they didn’t necessarily know?” he said. “I’m pretty tough on them when it comes to that. The big thing is students want to write the universal ‘you’ in a poem. I try to push them to write the ‘I’ and why that’s important.”

They talk about imitating their favorite poets but filtering that through their own narrative. Daye weaves music into his poetry courses, using examples of Bob Dylan singing “The Times They Are A-Changin’” — then Nina Simone making the song a whole new thing.

“I try to get them to think about the images that evoke something in them. I enjoy that UNC students are not afraid to challenge the way they think about something,” he said.

Mapping meaning in the world

Society has often turned to poets to make meaning of the world. Does Daye feel a heightened sense of urgency to make art that matters amid a global pandemic and renewed attention to the long-term injustices faced by people of color?

“This idea of trying to move somewhere safely in the world has been happening forever. Yet it’s wild to me that the poems in Cardinal seem so necessary right now,” he said. “What you’re making and how it speaks to the world, there’s pain that may come with that.”

From “Carry Me

after Langston Hughes”:

I followed the shimmer far down a road I still haven’t found

the ending to. I picked up my life

my mother sewn a map to the back of—

so one day I’d lay it out and travel back

to the flat land of eastern North Carolina.

A map to land where my body will die,

where my ghost won’t ride the trains all night,

count steps from liberty to home.

Daye said he has never written a “poem of the day” in response to what’s making front-page news. (He’s also never been a poet who writes in a coffee shop — it’s the outside world that beckons him: porches, birds flying, a neighbor’s car playing music.)

“If you are an artist in the world, and you are looking at the world and trying to make meaning of it, these things can’t help but show up if you’re looking and paying attention,” he said.

It’s about listening and learning to walk in somebody else’s shoes. It’s about showing humanity and not shying away from the good and the bad.

“Art, all art, teaches us empathy,” Daye said.

Read Daye’s “By Land” from Cardinal (Copper Canyon Press, October 2020) in our Finale feature.

Celebrate a virtual book launch for Daye’s new book on Oct. 16.

Watch a video of Daye reading his poem, “Miss Mary Mack Introduces Her Wings.”

By Kim Weaver Spurr ’88

Published in the Fall 2020 issue | Features

Read More

A MythBusters approach to life

For up-and-coming astrophysicist Ben Kaiser, a desire to figure things…

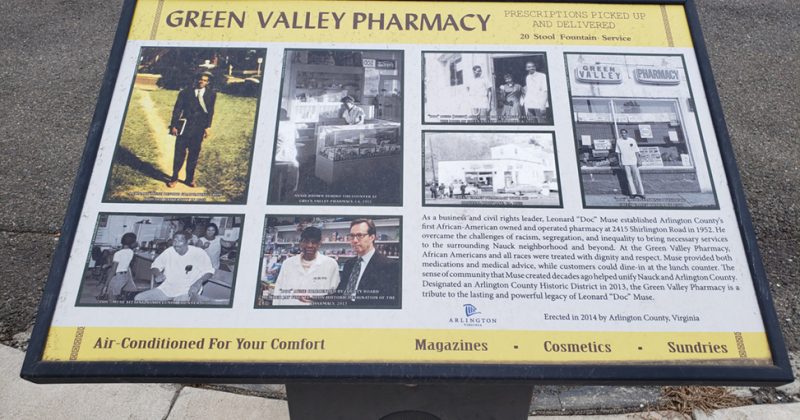

Southern Futures: Exploring intersections of class and race in Green Valley

Moriah James in Washington, DC. Graduate student Moriah James was…

Treul, Marinelli to lead Program for Public Discourse

Sarah Treul and Kevin Marinelli have been tapped to lead…