A mysterious disease. Stressed-out health care workers. The race for a vaccine. Southern Oral History Program students probe memories of an earlier pandemic to better understand the current one.

Oral history is a way to put yourself in someone else’s shoes,” said Sara Wood, project manager for the Southern Oral History Program. SOHP is part of the Center for the Study of the American South. (photo by Donn Young)

Oral history is a way to put yourself in someone else’s shoes,” said Sara Wood, project manager for the Southern Oral History Program. SOHP is part of the Center for the Study of the American South. (photo by Donn Young)

When scholars at the Southern Oral History Program were considering new projects for graduate students to undertake last spring, they thought that interviewing people about the polio epidemic — the disease wasn’t eradicated in the United States until 1979 — could provide a lens for understanding COVID-19.

Since 1973, SOHP has preserved the stories of people from all walks of life, from mill workers to civil rights activists, in an online archive through University Libraries’ Southern Historical Collection. Based in the Center for the Study of the American South, the program has the motto: “You don’t have to be famous for your life to be history.”

Prepping for the project

“He was in the hospital about 26 days. … I had to hand him over to a nurse, and I thought I would choke to death, to give him up when he’d never been away from me and to hand him over to strangers. It was hard.” – Ruby Merritt on her son, Wendell, contracting polio in 1943 at age 3.

Graduate field scholars Susie Penman, left, and Caroline Efird interviewed people about their experiences with polio. They also probed research materials like these in the Southern Historical Collection in Wilson Library. (photo by Donn Young)

Graduate field scholars Susie Penman, left, and Caroline Efird interviewed people about their experiences with polio. They also probed research materials like these in the Southern Historical Collection in Wilson Library. (photo by Donn Young)

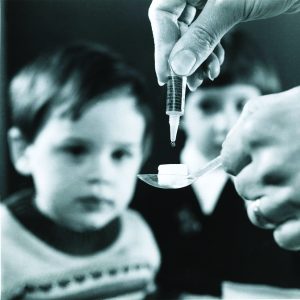

SOHP provides fellowships to graduate students who receive oral history training while they work on research projects. To prepare for the Polio Project, the field scholars first consulted the archives — probing the rich database of existing “life history” interviews to find audio clips like the one with Ruby Merritt as a way of gaining background information before embarking on fresh interviews.

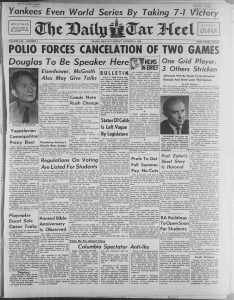

They turned to historical newspapers in Digital NC’s archive to find out how the polio epidemic had affected North Carolina (and UNC-Chapel Hill), and they read the 2006 Pulitzer Prize-winning book, Polio, An American Story: The Crusade that Mobilized the Nation Against the 20th Century’s Most Feared Disease.

Archival Daily Tar Heel and Summer School Weekly headlines struck a familiar chord with what the UNC community has been facing with COVID-19. In 1952, “Polio Forces Cancellation of Two (Football) Games,” and in 1957, “Polio Total Jumps; Students Urged to Get Shots.”

Archival Daily Tar Heel and Summer School Weekly headlines struck a familiar chord with what the UNC community has been facing with COVID-19. In 1952, “Polio Forces Cancellation of Two (Football) Games,” and in 1957, “Polio Total Jumps; Students Urged to Get Shots.”

Four graduate field scholars conducted new interviews in spring 2021 with residents of Carolina Meadows, a Chapel Hill retirement community, as well as other people.

“We asked them questions such as: ‘What was polio like? Who helped you if you got sick? What was it like to be isolated from others?’” said Susie Penman, a graduate field scholar and Ph.D. student in American studies. “They shared that as a kid in the summertime [when the virus seemed to peak], they were not allowed to go swimming, and you didn’t have social media and other things to keep you occupied while inside. It was a different kind of struggle to be isolated.”

Penman became so interested in the project that last summer she reached out to people in “post-polio” support groups. Similar to those dealing with long COVID-19, these polio survivors are coping with the lasting effects of polio.

In June, Penman interviewed Beverly Foster, former longtime director of the undergraduate program in the UNC School of Nursing. Foster remembered an uncle who had polio, which affected his ability to pursue a career as a musician, and an English teacher who used crutches as a result of polio. As a practicing nurse in the late ’60s, she treated children with polio at a clinic on the U.S.-Mexico border.

Although the field scholars usually conduct interviews in person, in many instances they had to adapt their research methods during the pandemic.

Caroline Efird, a Ph.D. student in the department of health behavior at the Gillings School of Global Public Health, learned to use Zencastr, a high-quality audio recording platform.

“I did feel like we were able to make genuine connections with people, even if only virtually,” she said. “Even though we weren’t sitting in people’s living rooms, we were still able to be present with them in that digital space.”

Pandemic parallels

“It was a hot, hot summer, up to 100 degrees. I was given maybe two or three patients in iron lungs to look after … being 5 feet tall, I had to stand on a stool to put my hands through the portholes to do nursing care for the patients.” — Virginia Wood, on treating patients in the ’50s and ’60s at North Carolina Memorial Hospital (SOHP archives).

Margaret Truman (seated, center) in a 1948 White House broadcast for the March of Dimes. (courtesy of National Archives and Records Administration)

Margaret Truman (seated, center) in a 1948 White House broadcast for the March of Dimes. (courtesy of National Archives and Records Administration)

Stressed-out health care workers. Hope for a vaccine. Struggles over quarantining and isolation. Anxiety over the unknown. Community resilience.

Some familiar themes began to emerge between the polio and COVID-19 pandemics as researchers culled through archival materials (like Virginia Wood’s interview) and talked to new people.

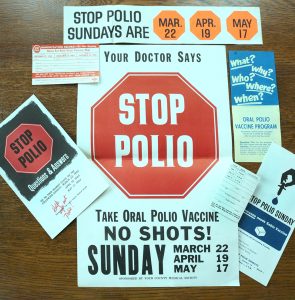

There were differences, too. “We also discovered that vaccines were often given at schools — schools were such a central hub for communities back then; they were a connection to public health and safety,” said Sara Wood, an oral historian and project manager for SOHP who has produced stories for National Public Radio and the Southern Foodways Alliance.

Efird interviewed William Earl Thompson, a retired minister and resident of Carolina Meadows, who experienced polio outbreaks in 1944 and 1948 in Statesville. He remembered that the nearby town of Hickory became a focal point for the epidemic.

“Polio was such a mysterious thing. Nobody knew where it came from. …. But I was aware as an 8-year-old child that there was a fearful thing happening nearby,” said Thompson, who recalled trucks spraying DDT in the streets because people thought polio might have been spread via mosquitoes. He also recalled setting aside 10 cents of his allowance each week for the March of Dimes.

Seth Kotch, director of SOHP and an associate professor of American studies, said the “Miracle of Hickory” was a great example of a community coming together. In June 1944, a field hospital was quickly built in Hickory with nurses recruited from local colleges. The staff of the Hickory Emergency Infantile Paralysis Hospital treated 454 children who contracted polio, according to a 2018 Our State magazine article.

“It’s a story of people overcoming adversity,” Kotch added. “North Carolina was really the site of a great success story even as it was the site of struggles. … As we try to understand our present moment better, what does it take to unite a community around a solution to a common problem?”

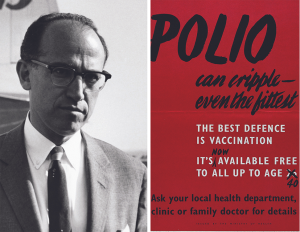

Kotch noted that his father, Jonathan, a retired pediatrician and UNC public health professor, grew up in New York and was a “polio pioneer.” In 1954, he was among the first children to receive the polio vaccine developed by Jonas Salk. His father attended elementary school with Salk’s niece, and for years proudly carried a polio pioneer identification card with him.

“In many ways, polio became the perfect candidate to help us learn about COVID,” Kotch said. “How can we understand what’s going on all around us by looking to our past? That is one of the core missions of a historian.”

A humanities lens

Efird said even though she is a public health scholar, she appreciates the value of humanities research.

“I love how oral history and qualitative research centers the voice of the people who are experiencing these things,” said Efird, who also previously served as a graduate research consultant for an Honors English class on “healers and patients.” “I hope in my career to continue to focus my work through a humanities lens. How we can use both qualitative and quantitative research to meet the needs of the people who are receiving the care?”

“I love how oral history and qualitative research centers the voice of the people who are experiencing these things,” said Efird, who also previously served as a graduate research consultant for an Honors English class on “healers and patients.” “I hope in my career to continue to focus my work through a humanities lens. How we can use both qualitative and quantitative research to meet the needs of the people who are receiving the care?”

Wood said the work of graduate students is central to SOHP’s mission.

“We started this as a pilot project to see what would happen if we scratched the surface. A lot of surprising stories and experiences came up, more than I think we initially expected,” Wood said. “Oral history is a way to put yourself in someone else’s shoes.”

Listen to excerpts of polio interviews curated from the SOHP archives at go.unc.edu/polio-project.

By Kim Weaver Spurr ’88

Published in the Spring 2022 issue | Features