Undergraduate student Joey Carter wades into Albemarle Sound to deploy instruments for research on how waves are impacting living shorelines. (photo by Johnny Andrews)

Union of geological and marine sciences disciplines erases artificial boundaries.

Rivers flow from a continent’s heart into the vast oceans, pumping weathered bits of rock and clay onto broad beds of sediment that form our continental shelves. Oceans change the shape of our coastlines in a relentless wave-driven dance of erosion and deposition. Coastal floods and storm surges alter people’s lives.

The new department of earth, marine and environmental sciences, which goes by the acronym EMES, reflects these natural connections between land and sea. Launched in July, it unites the University’s department of marine sciences, the department of geological sciences and the Institute of Marine Sciences (IMS) in Morehead City, North Carolina.

The fusion reflects the University’s broader approach to connect faculty across disciplines with the goal of solving deeply rooted societal challenges. Convergent research between faculty in marine sciences and geology was already happening. The new department will bring together more than 30 faculty, nearly 70 graduate students and numerous postdocs, and research and technical staff.

The merger is being phased in: Over the next two years, EMES will introduce its new curriculum for its undergraduate degrees and program minors as well as start recruiting graduate students for admission to a single graduate program.

These five UNC researchers exemplify the sweeping breadth of connections among land, rivers, coasts and oceans.

Rivers, sediment, marshes and estuaries

Emily Eidam has boarded 320-foot global ice breakers, 12-foot inflatable rafts and pushed off in kayaks to learn how land-based mud ends up in the oceans — and what happens to it next.

“Most people think that studying mud in the ocean sounds boring. But I’m usually able to sell students on the idea by the time we talk about submarine landslides and illegal sand mining,” said Eidam, an assistant professor who describes herself as “a coastal sedimentologist and marine geologist.”

She and her team spent time this past summer in Harrison Bay, Alaska, deploying instrumented moorings in the Arctic Ocean. Eidam is studying how the sediment generated from coastal erosion is distributed across the continental shelf by waves and currents.

How fast are these particles of sediment transported, how much river-borne sediment do continents shed and where exactly does it all go? The research team uses optical and acoustic sensors to study sediment particles in the water column, trying to understand the process of sediment transportation.

Sometimes this means studying inland rivers, but the work often extends onto the continental shelves. These broad sediment traps are like textbooks in that they record past sediment deposition, along with any changes in how much sediment is generated from the landscape.

“We can use tracers to figure out how much sediment has settled in an area over the last two months or a year — or 50 years,” Eidam said.

Understanding sediment transportation can help communities plan for dredging harbors, evaluate habitat changes in sensitive ecosystems or locate resources for beach nourishment projects.

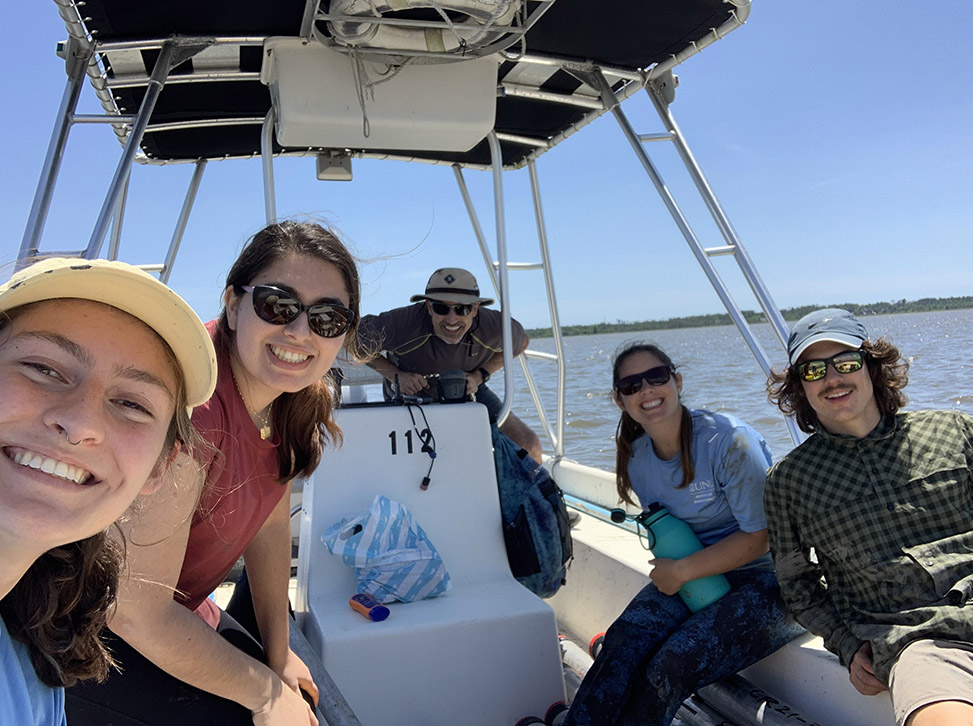

Ph.D. candidate Molly Bost, second from right, on her way to an oyster reef in the Newport River to take cores through an old reef system that used to form a bridge across the river at low tide. (photo by Naomi Nice)

Ph.D. candidate Molly Bost, second from right, on her way to an oyster reef in the Newport River to take cores through an old reef system that used to form a bridge across the river at low tide. (photo by Naomi Nice)

Molly Bost, a Ph.D. candidate, takes a similar approach in navigating the interface between geology and sedimentology. She studies the geology of salt marshes at IMS, which provides access to both coastal marshes and a laboratory in one place.

“I’m interested in the vertical growth of marshes and oyster reefs, and the inherent resilience of that growth against sea level rise and storms,” Bost said.

Bost uses sediment cores and remote sensing to study coastal habitats. She seeks to understand how growth of the habitats has changed over the past 1,000 years. Knowing their past will inform how to manage and conserve reefs — and retain the beneficial services they generate, such as buffering the coast against storm surges.

“There is a lot of research on artificial oyster reefs, but it’s surprisingly sparse on natural reefs,” Bost said. “I’m trying to understand what drives growth of natural oyster reefs — the tidal frame, proximity to other habitats and at what elevations — and use that to guide restoration efforts.”

It is essential information given the uncertainties surrounding projected sea level rise driven by climate change.

Bost is also passionate about outreach to the state and in engaging a diverse pool of students in this type of work.

She started an outreach program called GEST, which stands for Growing Equity in Science and Technology.

GEST brings girls and young people of color to IMS with the goal of instilling confidence in learning about science. Experts talk to them about career paths in academia or governmental organizations, such as the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

“We should engage the stakeholders and people who live in the areas we study,” Bost said. “They should be a part of the process, too.”

River and coastal floods

Assistant professor Antonia Sebastian (pictured at right) also investigates processes at the juncture of rivers and coasts. Her research lab focuses on watershed hydrology and flood hazards.

Assistant professor Antonia Sebastian (pictured at right) also investigates processes at the juncture of rivers and coasts. Her research lab focuses on watershed hydrology and flood hazards.

“My research embodies the natural links in EMES because I work at the interface of the land and the ocean,” Sebastian said. “I already blend geological and marine sciences in my work, but EMES will strengthen these collaborations and solidify them.”

Sebastian is examining the physical drivers of compound flooding in coastal areas. Compound floods occur when multiple events or climactic extremes happen simultaneously or in quick succession, amplifying or accelerating floodwaters. (Think of the devastating storm surge and rainfall of Hurricane Florence that flooded eastern North Carolina communities.)

Her lab also studies how flood risks change over time and space as a function of urbanization and climate change. “It’s about looking at earth surface processes and how they evolve over time, but also how the human and natural systems interact to drive flood impacts to society,” Sebastian said. “We are trying to understand how climate and land use changes combine to exacerbate flooding in coastal zones.”

For example, some of her prior work from the Houston-Galveston region of Texas suggested that community land development decisions ultimately harmed the ability of natural systems to protect against flooding. This has important implications for the long-term resilience of coastal communities.

Climate change and fisheries

We tend to think of the effects of climate change upon land-based systems, but its effects are already changing offshore water temperatures to such a degree that fish are on the move.

Associate professor Janet Nye specializes in studying the effect of climate change on fisheries, and her work has implications for commercial and sport fishing alike.

Take summer flounder, for example. Her work has shown that these fish were shifting northward due to warming waters. This was confirmed when commercial fishing boats that previously caught summer flounder off the Carolina coast found they needed to motor all the way to waters off New Jersey.

“For the past decade I have focused on how fish populations are shifting their distributions,” said Nye, who is also based at IMS. “Most fish species off the East Coast have moved northward. That means that fishermen must adapt by either following the fish further away or switching to different species altogether.”

That’s a big shift, and one that has deep implications for the people who profit and prosper from North Carolina’s commercial fishing industry, which in 2019 netted nearly 53 million pounds of fish and crustaceans worth $86.6 million.

“We know surprisingly little about the temperature ranges of most species,” Nye said. “We take this basic information and scale it up to understand where the fish will be in the ocean, and where they may be 20, 50 or 100 years from now given climate change.”

Learn more about Janet Nye’s research.

Geological time and experiential learning

Professor Eric Kirby and colleagues in the French Alps near La Grave, France. (courtesy of Eric Kirby)

Professor Eric Kirby and colleagues in the French Alps near La Grave, France. (courtesy of Eric Kirby)

EMES is being led by professor Eric Kirby, who helped manage a similar fusion of departments in his former position as an associate dean at Oregon State University. Kirby’s own research interests center on planetary-scale questions of how mountains grow, erode and decay. His work has taken him from the Appalachian Mountains in Pennsylvania to the Himalayans and the Tibetan Plateau.

“The way the solid and fluid earth interact over millions of years governs the trajectory of things like the composition of the oceans,” Kirby said. “It’s all connected; it’s just a question of the time and spatial scales over which we explore these questions.”

Kirby says EMES will offer a learning experience to students which emphasizes the connections across land, sea and time. He and other faculty are working to formalize interdisciplinary paths for students to study topics at the intersection of marine and geological sciences. He also envisions that EMES will offer its students enhanced experiential learning opportunities.

“Our faculty widely share a recognition that in earth and marine sciences, experiential learning is baked into everything we do,” Kirby said. “The problems are ‘out there,’ accessible by ship, on hiking or increasingly through remote sensing. There is important lab work that goes along with it, of course, but bringing students into the field is something we value.”

EMES faculty are discussing ways to increase student opportunities at IMS with this in mind.

“We think of geology as being about rocks, and we think of marine sciences as being about water,” Kirby said. “But they are connected. Any separation you try to draw is really an artificial boundary. The hope is that we allow those connections to blossom and lead to new discoveries, for students and faculty alike.”

By DeLene Beeland

***

Roberts-Watson Family Environmental Scholars Program

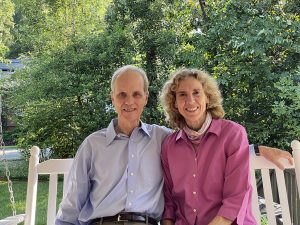

The newly formed department of earth, marine and environmental sciences received a vote of confidence from College alumni Jennifer Watson Roberts ’82 and Manley Roberts ’80, who have created the Roberts-Watson Family Environmental Scholars Program.

The program will support scholarships for high-achieving juniors and seniors majoring in earth, marine and environmental sciences, including students in the environment, ecology and energy program, with the goal of building a more inclusive scientific culture in the department.

Funding for high-impact summer experiences such as participation in faculty-mentored research, study abroad programs, credit-bearing internships or field work will also be provided for recipients who maintain a 3.0 GPA and who have financial need. The scholarship’s summer experiential learning opportunities could include field experiences in Morehead City and other parts of North Carolina, Thailand, the Galapagos and elsewhere around the globe.

Jennifer and Manley Roberts (pictured at right) established the fund to combine their passions for finding solutions to the most challenging resource issues facing our planet and creating more opportunities for students who enhance the diversity, equity and inclusion of the department of earth, marine and environmental sciences.

Jennifer and Manley Roberts (pictured at right) established the fund to combine their passions for finding solutions to the most challenging resource issues facing our planet and creating more opportunities for students who enhance the diversity, equity and inclusion of the department of earth, marine and environmental sciences.

“As alumni of UNC, we both love what the University has done for our lives, and we want more students to have the same great opportunities we did,” Jennifer Roberts said. “We know that environmental science is increasingly important, and North Carolina is front and center for being at risk from extreme weather. We hope our scholarship will help more diverse students enter this field, to research the ways we can mitigate the impacts of extreme weather for our food supply, our health, our wallets and our lives.”

Support for programming designed to foster a sense of community among scholars and facilitating connections with alumni and leaders making a mark in the field of environmental science will also be supported by the Roberts-Watson Family Environmental Scholars Program.

The department recognizes the importance and value of diverse student perspectives in the classroom and in experiential learning settings.

“The Roberts’ generosity in establishing this endowment will help ensure that the varied experiences and viewpoints of students in EMES will enrich everyone’s experiences within the department,” said Eric Kirby, department chair.

Published in the Fall 2021 issue | Features

Read More

Expand your bookshelf: More books by College faculty and alumni

North Carolina: Land of Water, Land of Sky (UNC Press,…

New gift marks the importance of support for clinical psychology graduate students

As the No. 2 ranked clinical psychology graduate program (U.S….