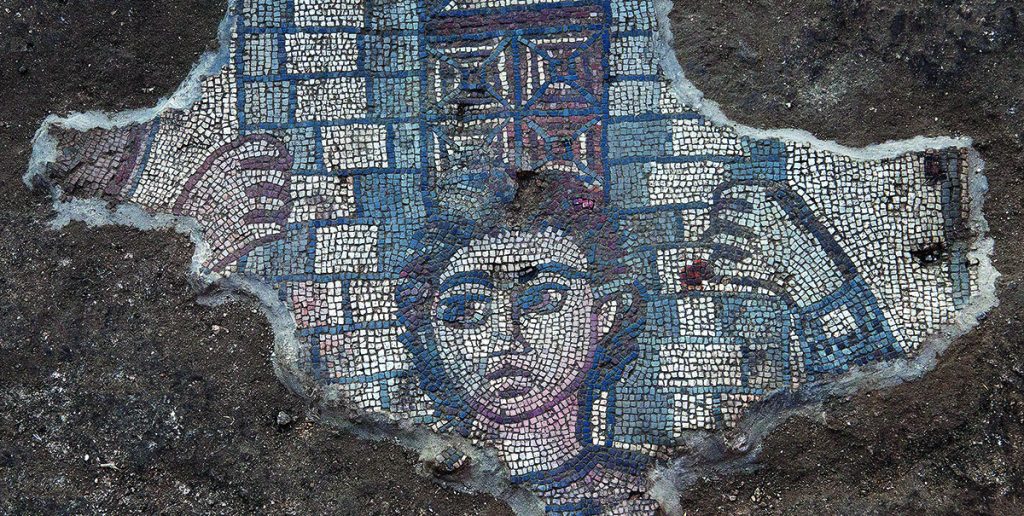

A UNC-led archaeological team in Israel's Lower Galilee has uncovered stunning biblical mosaics at an ancient synagogue, like this one of Samson carrying the gate of Gaza on his shoulders from Judges 16:3.

A decade-long, UNC-Chapel Hill-led archaeological dig in Israel’s Galilee has revolutionized our understanding of ancient Jewish religious and cultural life.

The email Carolina archaeologist Jodi Magness sent her colleague Karen Britt in the summer of 2012 read: “Mosaics 911 Emergency. Need You Here.”

Magness, Kenan Distinguished Professor for Teaching Excellence in Early Judaism, was in the second season of her dig at Huqoq, an ancient Jewish village in Israel’s Lower Galilee.

Britt, today an assistant professor at Northwest Missouri State University and a mosaics expert, was on a research fellowship in Jordan but immediately agreed to help. Magness met her at the northern border crossing and briefed her on the drive to the site, which is about four miles northwest of the Sea of Galilee, atop a rocky hill.

The surprise find — a colorful mosaic made up of tiny limestone cubes called tesserae — showed two female faces flanking a circular medallion with a Hebrew inscription. Another key find that same summer, both part of a synagogue floor: a mosaic depicting the biblical story of Samson placing torches between the tails of foxes.

The next year, a mosaic showing Samson carrying the gate of Gaza on his shoulders was uncovered, then in 2023 — the last summer of the dig — a slain Philistine soldier. The three scenes from Judges 15-16 complete what scholars are calling a “Samson cycle.”

During their years at Huqoq, Magness, a host of international specialists and hundreds of field school students from multiple consortium schools would continue to uncover myriad amazing finds, including the first non-biblical story ever discovered in an ancient synagogue. [See more of these extraordinary finds at the end of the story]. Britt has stayed with the project and collaborates with a historian of Judaism in researching the mosaics. The discoveries are transforming what we know about Jewish life in ancient Palestine.

Magness began digging at Huqoq in 2011 because of big research questions she was hoping to answer. There is nothing in early rabbinic literature that would have prepared her for a synagogue like Huqoq, she said, and that’s where archaeology is helping to fill in the gaps and illuminate the dynamism and complexity of Jewish life 1,600 years ago.

“Most Galilean-type synagogues have been dated to the second and third centuries, but we have evidence of a late fourth-early fifth century synagogue at Huqoq,” said Magness, who is a professor in the department of religious studies and a faculty member in the Carolina Center for Jewish Studies and the curriculum in archaeology. “This is significant because if these buildings were built in the earlier period, they were built in a pagan Roman context. Our synagogue was built when the Roman Empire was under Christian rule, a period that scholars believed was oppressive to Jews and during which Jewish settlements were declining. Yet clearly this village was flourishing and prospering.”

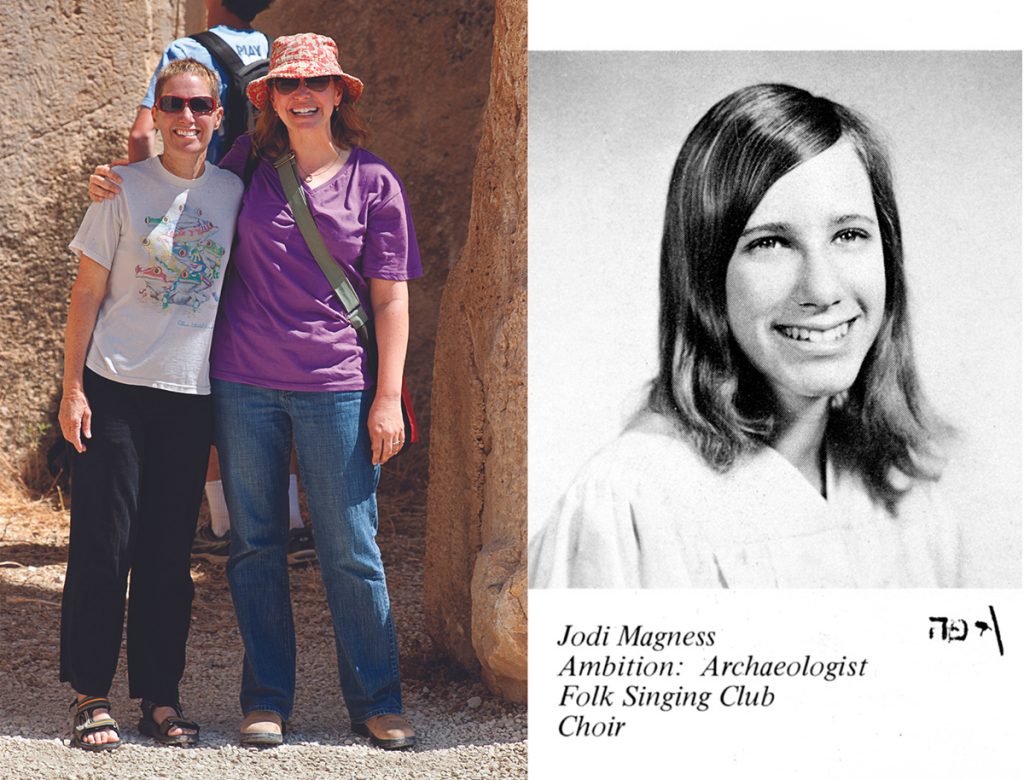

Ambition: archaeologist

Magness knew she wanted to be an archaeologist at age 12, sparked by the fossils she was finding at Girl Scout camp and a seventh-grade history teacher who introduced her to ancient Greece. In ninth grade, her yearbook photo caption read: “Ambition: Archaeologist.”

After falling in love with Israel during a tour in summer 1972, Magness left Miami to finish high school at Midreshet Sde Boker in the Negev desert, then completed her undergraduate degree at Hebrew University of Jerusalem. For a brief period, she thought she would go to law school — she was accepted into the University of Florida and the University of Miami — but a standing-room-only lecture at an Israeli institute about the discovery of the Roman Cardo in Jerusalem — the ancient city’s main thoroughfare — affirmed her original passion. She did not return to the United States.

Instead, she decided to work at the Ein Gedi field school for a while as a tour guide and naturalist — “that phone call to my parents was not a great call,” she said with a laugh — and after four years, she enrolled at the University of Pennsylvania for her doctorate.

Magness joined the Carolina faculty in 2002 from Tufts University. She is known as a worldwide expert on Masada (she co-directed the 1995 excavations in the Roman siege works there), Qumran and the Dead Sea Scrolls and ancient Palestine. Over the last 30 years, she has published 13 books and numerous articles and book chapters, been inducted into the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, and has participated in over 20 excavations in Israel and Greece. Her forthcoming book, Jerusalem Through the Ages: From its Beginnings to the Crusades (Oxford University Press), a detailed account of one of the world’s holiest and most contested cities, will be published in the spring. The award-winning teacher and scholar is also past president of the Archaeological Institute of America.

Her work resonates with both academics and popular audiences. She was featured in a National Geographic IMAX film titled Jerusalem and was a consultant and an on-camera expert in the Nat Geo series The Story of God with Morgan Freeman.

“There’s a never-ending stream of interesting questions about this region. From an archaeological point of view, Israel is the most extensively explored country on Earth,” she said.

Hooked on Huqoq

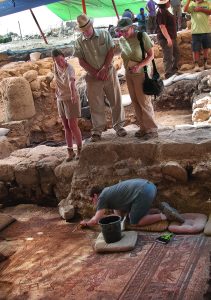

At the kibbutz where the field school participants stay, the alarms go off around 4 a.m. Time for a quick cup of coffee or tea, then students sleepily board the bus for a 15-minute ride to Huqoq. After drop-off, there’s a brief hike to the site, illuminated by flashlights, then they unload the water jugs and breakfast items off a supply truck and put up shade cloths to shield everyone from the glare of the sun.

Life on a dig is a hot and dirty job, a lot of it done with pickaxes and hoes.

“I think the general consensus is that archaeology is a library, bookish job, but it’s more like construction, honestly,” said Chrissy Stamey, a UNC senior anthropology and archaeology major who returned for her second season to Huqoq last summer. “You really get to know people through very hard, physical work. And I love it so much.”

For her initial trip in 2022 — her first time out of the country — Stamey received private support from the Lori and Eric Sklut Undergraduate Experiential Learning Fund. “The experience opened so many doors in my life and changed the trajectory of my education,” she said.

A couple of hours into the dig morning, the smells of breakfast — cheesy eggs, French toast, omelets, fruit, salads, pita bread — begin to waft over the site.

“The most glorious sound that you’ll ever hear on a site is Jodi’s voice at approximately 8 a.m. yelling ‘breakfast’ at the top of her lungs,” said Jada Enoch. “It still makes me smile to this day.”

Enoch, a 2023 graduate who majored in peace, war and defense and religious studies, was also a Huqoq returner. She and Stamey were given extra responsibilities during their second season, including assisting the project’s ceramics specialist.

There’s another break around 11 a.m. — fondly called “elevensies” — featuring watermelon for hydration. By noon, students have worked a full day. But their work is not over yet. Pottery sherds are delivered to pottery expert and UNC M.A./Ph.D. classics alumnus Dan Schindler for washing and cataloguing, coins and other artifacts are registered in the database, and students participate in lectures and field trips throughout their time in Israel.

“I’ve had an opportunity to network through this program and to strengthen my academic relationships with incredible faculty members I never would have had the opportunity to meet,” said Enoch, who also received scholarship support for her study abroad experience and is taking a gap year before applying to graduate school.

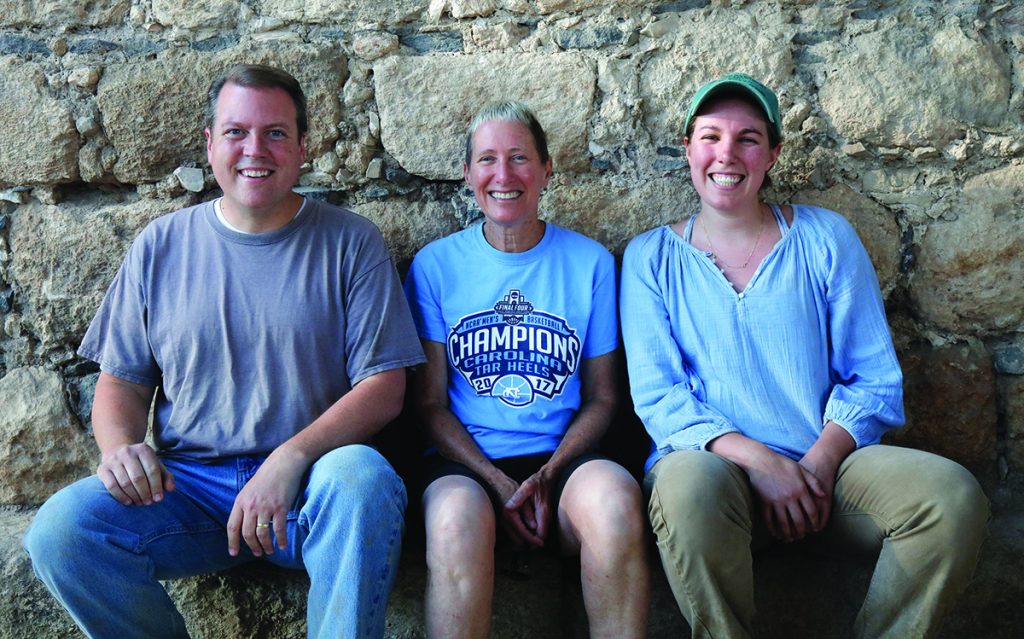

Jocelyn Burney may take the prize, though, as the ultimate Huqoq alumna. She got hooked at age 19 as a Carolina undergraduate, participated in the first excavation season, and has continued ever since, through completing her Ph.D. under Magness’ guidance last May. It was her final summer as an area supervisor on the dig; she began her academic career this fall as an assistant professor of ancient Mediterranean religion at the University of Missouri. She’ll be bringing her experience at Huqoq into her classes on “The World of the New Testament” and “Christianity and Paganism.”

The experience has made a huge impression on Burney as a scholar — but it has impacted her personal life, too.

“I actually met my future husband on the dig; we met in the UNC field school in 2013,” she said.

An intriguing puzzle

In 2021, Nat Geo named the Huqoq mosaics among its list of “100 Archaeological Treasures of the Past.” Every year, the finds have made headlines in national and international media.

Britt said for her, Huqoq is “the project of a lifetime.”

“There are people who dream of the opportunity to work on material that is this groundbreaking,” she said. “I will work on other digs, but I can’t imagine I will have an opportunity to work on something that is poised to make such an important contribution to our understanding of art and archaeology of the late Roman period.”

Scholars say the range of motifs depicted in the mosaics is unparalleled in any other ancient synagogue, but the building itself is quite extraordinary, too, with colorful painted plaster adhering to some of the columns.

“I like to say it was the world’s kitschiest synagogue,” Magness said.

In fact, the team has discovered two synagogue buildings at Huqoq — one built during the medieval period about 1,000 years later on top of the original one. That 14th century C.E. building appears to be the first Mamluk period synagogue ever discovered in Israel.

It is Martin Wells’ job to figure out how to reconstruct those two synagogue buildings. He’s been the architectural specialist at the site for six seasons and is an associate professor at Austin College in Texas. Wells has also brought his students to the field school as part of the Huqoq consortium.

That second building reused many of the features of the first, and the floor in the later synagogue helped to preserve the mosaic floor of the earlier one underneath.

“We have evidence of these supporting buttresses where they had to cut through the mosaic floor, but only where they needed to. They preserved what they could, which is amazing,” said Wells. The 2022 and 2023 excavations also brought to light an enormous paved courtyard surrounded by a row of columns known as a colonnade to the east of the synagogue.

“It has left us a very intriguing puzzle to solve, to figure out where all of the pieces go,” he added. “Archaeological discovery and understanding come with the trowel and the brush, the literal moving away of dirt to uncover things. But there’s also the intellectual ‘brushing away,’ when you discover how things fit together. And that’s the best.”

Excavation and publication

The site was backfilled for preservation in summer 2023 and turned over to the Israel Antiquities Authority and the Jewish National Fund for future tourism development.

On that last day, Magness’ husband, photographer Jim Haberman, took a photo of her on the east wall where he had also snapped a shot during the first dig season in 2011.

Burney, Magness’ former Ph.D. student, remembers that moment.

“Initially, that first year, there was just a little bit of wall — and dirt. This year, you saw that entire [65-by-50 foot] building behind her. It was really special.”

Magness’ colleagues also presented her with a surprise offering, an academic publication called a festschrift. The word, borrowed from German, is a celebratory volume of essays honoring an esteemed scholar.

Matthew Grey, a former Ph.D. student of Magness’ who is a professor at Brigham Young University, was one of the editors of the publication, “Pushing Sacred Boundaries in Early Judaism and the Ancient Mediterranean.”

Grey has been with Huqoq from the beginning — he became an area supervisor at the site after finishing his UNC Ph.D., and BYU is a consortium member. He has also brought his students to the field school.

“Jodi has a contagious enthusiasm for her work,” Grey said. “She’s been extremely influential to me as a scholar and a teacher. Her work captured my imagination about things I wanted to explore even further.”

As she reflected on her 11 years at Huqoq (there was a brief pause during the COVID-19 pandemic), Magness said that even though excavation has wrapped up, the real work is just beginning.

“The goal of archaeology is not excavation, it’s publication,” she said. “I have two shipping containers of excavated materials that need to be analyzed. My team and I will be coming back for years in the summers to Jerusalem to work on that material for publication.”

By Kim Weaver Spurr ’88, photos by Jim Haberman

Listen to a “Virtual Voyage” podcast about Huqoq with Jodi Magness.

Extraordinary Finds

The Huqoq mosaics depict many ancient biblical and non-biblical stories, including:

- The Samson cycle: Samson and the foxes, a slain Philistine soldier, Samson carrying the gate of Gaza. (Judges 15-16)

- The earliest known depictions of female biblical heroines Deborah and Jael. (Judges 4)

- A Hebrew inscription surrounded by human figures, animals and mythological creatures including putti, or cupids.

- The first non-biblical story ever found decorating an ancient synagogue (also featuring battle elephants) — perhaps the legendary meeting between Alexander the Great and the Jewish high priest.

- Two of the spies sent by Moses to explore Canaan carrying a pole with a cluster of grapes. (Numbers 13:23)

- A man leading an animal on a rope accompanied by the inscription “a small child shall lead them.” (Isaiah 11:6)

- Figures of animals identified by an Aramaic inscription as the four beasts representing four kingdoms. (Daniel 7)

- Elim, the spot where the Israelites camped by 12 springs and 70 date palms after departing Egypt and wandering in the wilderness without water. (Exodus 15:27)

- A portrayal of Noah’s Ark. (Genesis 6-8)

- The parting of the Red Sea. (Exodus 14-15)

- A Helios-zodiac cycle.

- Jonah being swallowed by three successive fish. (Jonah 1)

- The building of the Tower of Babel. (Genesis 11: 1-9)

- A decorated border showing animals of prey pursuing other animals, including a tiger chasing an ibex (wild goat).

Published in the Fall 2023 issue | Features

Read More

Slavic center receives National Resource Center designation

The Center for Slavic, Eastern European and Eurasian Studies at…