Fifteen students in historian James Leloudis’ Honors undergraduate research seminar spent last semester in the University Archives, probing letters, financial ledgers and other records, to understand how the institution survived financially, in part, from the sale of enslaved people.

When the General Assembly chartered the University of North Carolina in 1789, it made no direct appropriation to support it. Instead, lawmakers gave the Board of Trustees the right to claim proceeds from the sale of escheats — property of people who died without heirs. To turn escheats — which sometimes included enslaved people — into cash, trustees appointed attorneys across the state to act as their agents in arranging sales.

Between 1790 and 1840, escheats accounted for 69% of the University’s income, said James Leloudis, history professor and Peter T. Grauer Associate Dean for Honors Carolina. Other sources included tuition and monetary gifts.

Fifteen students in “Slavery and the University,” an Honors course taught by Leloudis and history doctoral candidate Laurie Medford, spent hours in the University Archives in Wilson Library as they followed a trail of disparate documents to weave together stories of enslaved people’s lives and how the University benefited from escheated property. Philanthropic support from alumnus Gordon Golding helped to support Medford’s position. [See sidebar].

This second iteration of the class was part of the College of Arts & Sciences’ Reckoning: Race, Memory and Reimagining the Public University shared learning initiative in fall 2019. Taking a deep dive into one aspect of UNC’s ties to slavery was both a practical and a pedagogical strategy: it allowed students working together in teams to hone in on a specific topic and produce high-quality scholarship. They created research posters of individual case studies.

The unique financial arrangement of escheats illustrates a larger point that Leloudis insists many people misunderstand — the degree to which the institution of slavery shaped not only the economic life of North Carolina and the South — but also the nation.

Leloudis shared a quote from National Book Award-winning author, journalist and activist Ta-Nehisi Coates, who said, “We talk about enslavement as though it were a bump in the road, and I tell people it’s the road, the actual road.”

“In 1860, the value of enslaved people throughout the South was greater than the combined value of every railroad, bank and industrial enterprise in the United States,” said Leloudis. “So even in places that did not have slavery, slavery built the economy.

“I think you could apply that to the University. If you imagine slavery as just a ‘bump’ in our history, that is a fundamental misunderstanding.”

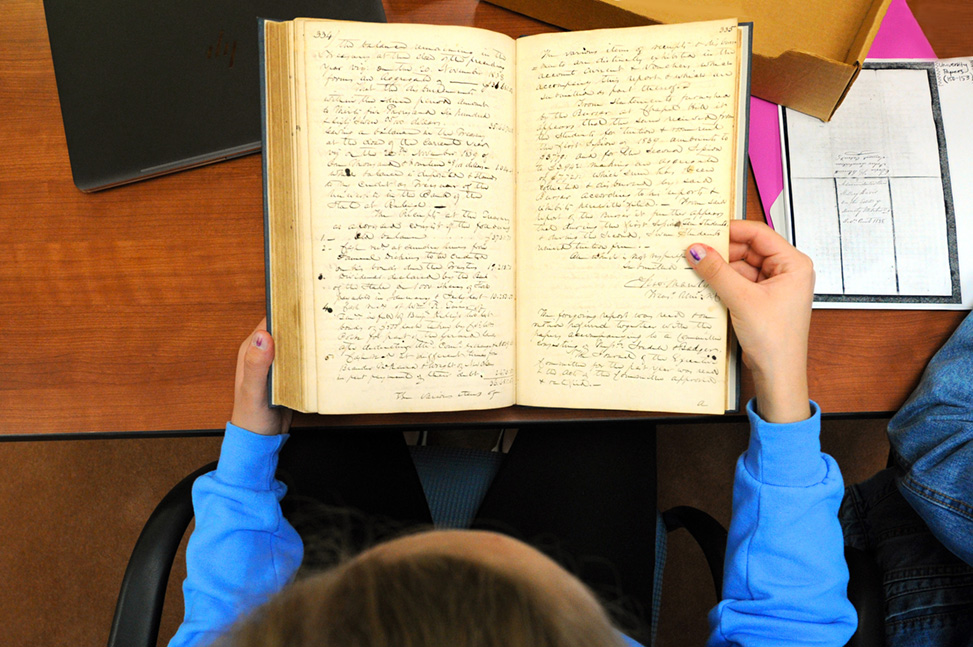

Leloudis said he was impressed with his students’ original research and their ability to condense complicated material into 500-word engaging stories. (photo by Donn Young)

Leloudis said he was impressed with his students’ original research and their ability to condense complicated material into 500-word engaging stories. (photo by Donn Young)

Case 1: Names Unknown — 1841

In 1841, through escheats, the University of North Carolina came into possession of a number of slaves including a “decrepid [sic] and infirm” old man who was unlikely to attract a buyer. What was the University to do with him? By state law, trustees were required either to care for him or to sell him. New Bern attorney James W. Bryan (class of 1824), an agent of the University, wrote to Board of Trustees treasurer Charles Manly (class of 1814) for advice. Manly suggested a familiar sales trick: Lump the “old trumpery” in with a younger slave and sell the two of them together. The fate of the man remains unknown, as the archival trail goes cold, but his life lay in the hands of the University.

Teamwork, time and tenacity

Lucy Russell, a senior public policy major, worked on the unknown 1841 case with her team. Every time they stepped into the archives reading room, Russell said, “We had to put on our 19th-century hat and leave our devices behind.”

Students had to decipher cursive handwriting and decode unfamiliar colloquial, legal and financial terms. Medford said for many students it was like learning another language. Sometimes that involved doing keyword searches in legal dictionaries and working painstakingly through 19th-century documents that were 15 pages long. Names were often spelled in multiple ways across documents.

For Russell’s team, that also meant a field trip to the UNC School of Law library.

“In the letter, the writer referenced a legal code from the 1830s, and he cited the exact page number in the general statutes. So we made an appointment with one of the law school librarians and she helped us navigate antique legal codes,” Russell said.

As it turned out, devices did come in handy — students often took photos of documents and used mobile apps such as CamScanner and Evernote to keep track of findings; they transcribed letters using their laptops.

Alexandra Tamvakis, a sophomore history and journalism major, recalled something Leloudis told the students early on in their detective work: “He compared archival research to doing a puzzle. Half of the pieces are missing and someone threw away the box top, and now you have to put the puzzle together and figure out the picture it makes. That’s a pretty good description of the challenges we faced.”

For one of her team’s cases, when the trail went cold, Tamvakis visited the State Archives in Raleigh to extend the research.

“I got to be on a friendly basis with the archivists there, and because of my experience at UNC I didn’t feel completely out of my depth,” she said. “Certain records were easier to find in the state archives — for example, a copy of a will we were looking for.”

Laurie Medford (left) and Lucy Russell discuss a case. (photo by Donn Young)

Laurie Medford (left) and Lucy Russell discuss a case. (photo by Donn Young)

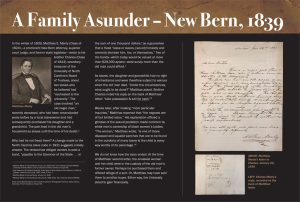

Case 2: A Family Asunder — New Bern, 1839

An older enslaved man who was later emancipated purchased his daughter and a grandchild, and they lived in his house as slaves until his death. Freeing them would have required posting two $1,000 bonds — a total equivalent to more than $58,000 today. In 1839, New Bern attorney Matthias Manly (class of 1824) wrote to his brother Charles, University treasurer, and asked about the daughter and grandchild who he believed should be escheated to the University. Charles gave a terse reply on the back of his brother’s letter: “Take possession and sell for cash.” No record

of the sale survives, but the University stood to gain financially from a family torn asunder.

A solemn topic, a personal journey

For students, sometimes the weight of what they were uncovering was tough to process. Marilyn Boutté, a sophomore public policy major, said that’s where the small teams really helped.

“We’d usually spend the last 30 minutes of class just talking through things,” she said. “It’s easy when we talk about slavery to talk about it institutionally and not as though it was about individual people. The language can sometimes be so cavalier.”

Boutté said Leloudis took students on a walking tour of campus on the first day of class, where they touched the bricks of buildings constructed by enslaved people. Leloudis calls it “traces of slavery.”

“The point was to help them recognize things that may otherwise be invisible. As we walk around the historic center of campus, there are traces of the institution of slavery everywhere you look,” Leloudis said. “These things we’re talking about become real when you see them in physical form.”

Russell is writing an Honors thesis about how slavery is being taught in North Carolina public schools. For her, the class was also part of her personal journey. Her great-great-great grandfather, Edward Porter Alexander, was a brigadier general in the Confederate Army, serving alongside Robert E. Lee. His family papers, around 3,000 items, are in the Southern Historical Collection in Wilson Library. Before she came to UNC, Russell and her mom and great-aunt had spent time going through the papers — sitting in the same reading room where Leloudis’ class would later be held.

“My maternal ancestors owned many enslaved people on their plantation in Georgia. The magnitude of my family’s involvement is unsettling,” she said. “I can’t control my heritage, but I can control how we as a family are grappling with that truthful history.”

Historian James Leloudis addresses students before they break into teams in the “Slavery and the University” class. (photo by Donn Young)

Historian James Leloudis addresses students before they break into teams in the “Slavery and the University” class. (photo by Donn Young)

Case 3: Anthony, Nelson, Jack, Betsy, Lewis and Tom — 1838-1840

Dorothy Mitchell’s personal possessions: one bed and furniture; two Dutch ovens; 27 lbs. of lard; four chickens; “six Negroes by the names of Anthony, Nelson, Jack, Betsy, Lewis and Tom.” When Mitchell, a resident of Northampton County, died in 1838, the enslaved people in her possession escheated to the University. Family petitioners challenged the claim. In March 1840, agent Bartholomew F. Moore (class of 1820) ended up closing the Mitchell case by selling each of the six enslaved people to multiple buyers — suggesting they may have been eventually resold to slave traders. The sales netted the University $3,631.19 (roughly $107,000 today).

Truth and healing

Leloudis was impressed with the patience, resilience and meticulous nature of the students’ work. They were asked to distill complex and convoluted cases into 500-word engaging stories.

When you’re reading about the enslaved people on Dorothy Mitchell’s estate, or, as in another case, about how Violet and her five children were sold, it can be hard, Leloudis said. “The tragic humanity of the stories stops you in your tracks.”

Tamvakis admitted it was “emotionally exhausting” but important work, and that she felt lucky to have had the opportunity.

“This reaffirmed my passion for making history accessible,” Tamvakis said. She is taking an introduction to public history course this semester.

Leloudis believes there’s also healing in the truth-telling.

“It’s the kind of effect that honesty has,” he said. “What students began to care about a great deal with the stories was the humanity of the people — calling their names.”

Leloudis is co-chairing the chancellor’s new Commission on History, Race and a Way Forward with Patricia Parker, associate professor and chair of the department of communication.

“There’s a lot of work to do,” he said. “If we want to be serious about healing and repair, we have to begin with honesty. And I think at the end of the day, to the degree that we can do that, it actually speaks to the strength of the institution.”

Boutté said walking around campus feels different to her now, but she wants to understand more about the history of the University where she will be spending so much time.

“If we really want to reckon with the past, we have to understand the history in order to move forward and to determine what moving forward might look like,” she said.

***

Sidebar: Pulling back the veil

Gordon Golding (right) believes that immersing undergraduate students in the archives allows them “to feel the dusty papers, to get a physical sense of history,” as it becomes real to them.

Gordon Golding (right) believes that immersing undergraduate students in the archives allows them “to feel the dusty papers, to get a physical sense of history,” as it becomes real to them.

An Honors research fund established by Golding helped to support history professor James Leloudis’ “Slavery and the University” course.

“They experience that these things we read about actually occurred and had an impact on human beings much like ourselves, despite differences in time, space and backgrounds,” said Golding, who received bachelor’s and master’s degrees in history from Carolina in 1974 and 1977, respectively, and a Ph.D. from Sorbonne University. He now lives in Paris.

Golding grew up in Charlotte, but through family research found out about his ancestral ties to Reuben Davis Golding, a highly successfully businessman and slave owner in Stokes County. This led him to conduct extensive research on people held in bondage in Stokes County. He has shared those findings with African American genealogical sites.

“The more I delved into my family history, the more I felt like I wanted to do something to pull back the veil that people have thrown over slavery, to show it in all its complexity and its pervasiveness, but also to reveal the often-denied humanity of enslaved people,” Golding said.

There are extensive UNC archives just waiting to be explored that can tell this story, he added.

“Encouraging scholarship and a fuller, richer version of history has been my over-arching goal, which I think is well embodied in Jim’s project.”

Story by Kim Weaver Spurr ’88

Published in the Spring 2020 issue | Features

Read More

A virtual museum of ancient N.C. history

Ancient North Carolinians is a new virtual museum that raises…

#Throwback: Happy 100 years, sociology

Sociology marks its centennial birthday this year. Learn more about…

Sharing Jewish life and culture across the state

Barry and Jan Schochet grew up in Asheville in the…