After retiring from Carolina, a biologist, a historian and an anthropologist find new creative inspiration and continue to mentor students, write books and conduct research.

Retired faculty members seldom actually retire — at least not in the feet-up, gone-fishin’ kind of way. Many are still actively engaged in academic pursuits, just a bit more selectively now.

“We cherish the fact that our retired faculty are Tar Heels for life. We are so grateful that they continue to contribute to Carolina and the academy with their scholarly pursuits, support of students and service to the campus community and beyond,” said Terry Rhodes, interim dean of the College of Arts & Sciences.

We recently chatted with three not-so-retired “retirees” to learn what they have been up to in their second acts.

Making time to mentor students

Ask Jean DeSaix what kept her at Carolina for 50 years and she replies without hesitation: her remarkable students.

Ask Jean DeSaix what kept her at Carolina for 50 years and she replies without hesitation: her remarkable students.

Through the years, she touched the lives of some 60,000 students in biology labs and classes large and small, consistently earning teaching accolades, including the prestigious Chapman Family Teaching Award and the Tanner Award for Excellence in Undergraduate Teaching.

Outside the classroom, DeSaix served as mentor and adviser to a host of undergraduate programs, ranging from Habitat for Humanity to Undergraduate Rural Medicine Scholars. In 2012, she was recognized with UNC’s Mentor Award for Lifetime Achievement.

With her husband, Peter (also a retired biology faculty member), DeSaix has mentored hundreds of Carolina Covenant scholars, a program that helps eligible low-income students graduate from UNC debt-free. They have worked with dozens of students each year, opening their home for meals and camaraderie, helping with course registration and advising on graduate school applications, among other things.

DeSaix describes their roles with the students simply as, “We love them.”

Because she wasn’t ready to leave the classroom entirely, DeSaix, who had earned the title of teaching professor, the highest rank for fixed-term faculty, spent three years teaching half-time as a move toward retirement. That provided room for activities such as helping the College Board develop Advanced Placement courses and the Biology Major Field Test, which tests student mastery of key concepts. She also revised her online biology course and a course for incarcerated students, both offered through the Friday Center for Continuing Education.

Two years ago, when DeSaix thought her deeply fulfilling classroom stint had ended, she had the opportunity to teach an honors biology course.

Later, she joined a campus discussion about the need for a health professions adviser — a role DeSaix knew well — and the outcome was a new one-credit hour course.

DeSaix worked with Abigail Panter, senior associate dean for undergraduate education, and Meg Zomorodi, clinical professor of nursing and assistant provost of interprofessional education, to develop “Pursuing Health Professions,” which explores various health care paths. When it was first offered last fall, 450 students registered within 72 hours, filling the 10-week course.

While she will no longer teach that course, DeSaix plans to help secure upcoming speakers and work with the new instructor to ensure a smooth transition.

In honor of DeSaix’s countless contributions through the years, the College established the Jean DeSaix Excellence in Teaching Fund.

Now fully retired from the classroom, DeSaix will continue to mentor students in the Rural Medicine and Carolina Covenant programs. If she finds that she misses the classroom, she said, “I’m persuaded to think there will be a way for me to get back into it.”

Bringing early research full circle

Jacquelyn Dowd Hall published her latest book in May, five years after she retired from the history department. But in a sense, the seeds for Sisters and Rebels: A Struggle for the Soul of America (W.W. Norton and Company) were planted at the beginning of her career. The book was reviewed in June by The New York Times.

The story of the three Lumpkin sisters has remained with Hall, the Julia Cherry Spruill Professor Emerita, ever since she interviewed the two younger sisters, Katharine and Grace, in 1974 — just a year after she came to Carolina as the founding director of the Southern Oral History Program.

The story of the three Lumpkin sisters has remained with Hall, the Julia Cherry Spruill Professor Emerita, ever since she interviewed the two younger sisters, Katharine and Grace, in 1974 — just a year after she came to Carolina as the founding director of the Southern Oral History Program.

Hall discovered the Lumpkin women while working on her dissertation. The sisters were born into a 19th-century slave-holding family and socialized into a staunch belief in white supremacy and the Confederacy. While the eldest, Elizabeth, held onto those beliefs, the younger sisters went on to become ardent supporters of Southern workers, black activists and women in post-suffrage America.

A grant from the Rockefeller Foundation in the 1970s enabled the SOHP to undertake a project on “Southern Women after Suffrage.” “It focused on women who walked through the door that suffrage opened in the 1920s and became activists, professionals and intellectuals,” Hall said.

As part of that project, Hall interviewed Katharine and Grace Lumpkin; Elizabeth had died some 10 years before. Hall stayed in close touch with Katharine, who ended up moving to Chapel Hill and, with Hall’s encouragement, left her papers to Carolina’s Southern Historical Collection.

Because the women were such private people, Hall waited to write the Lumpkin sisters’ still-timely story until they died.

“The dilemmas they faced are things that women and progressive Southerners are still dealing with,” Hall said. “History always has a bearing on the present.”

She couldn’t predict, however, that the overarching theme of Confederate memorialization — and the controversies surrounding race now gripping the country —would be so salient.

An award-winning teacher and scholar, Hall is a National Humanities Medal recipient and member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.

Her immediate agenda includes giving talks and readings focused on her latest publications, among them a piece about her mother for a book published earlier this year by UNC Press, Mothers and Strangers: Essays on Motherhood from the New South.

Creating a new model of sustainability in Colombia

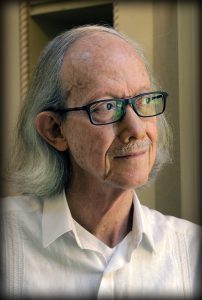

Some 40 years ago, Arturo Escobar switched paths from chemical engineering and biochemistry to international nutrition and food science. He wanted to understand why hunger existed worldwide.

As he quickly discovered, the problem wasn’t a lack of food as much as control over food production. The issue was sociopolitical — based on a model in which corporations developed huge swaths of land and small food producers were shoved to the wayside.

As he quickly discovered, the problem wasn’t a lack of food as much as control over food production. The issue was sociopolitical — based on a model in which corporations developed huge swaths of land and small food producers were shoved to the wayside.

Decades of globalization and economic development have exacerbated this disparity.

“Instead of having a system where people can actually grow food, they are pushed out to the cities under poverty conditions,” said Escobar, the Kenan Distinguished Professor Emeritus of Anthropology.

What’s more, the result has been immense damage to the environment, he noted.

Finding ways to reverse that damage requires fundamentally changing the economic and political systems that created the problem in the first place. That has been Escobar’s academic focus for the past three decades, 18 of those years spent researching, writing and teaching at Carolina.

Since Escobar retired in June 2018, he has directed much of his time toward designing a new model of sustainability for the Cauca River Valley in his native Colombia.

The area encompasses a lovely 500-kilometer valley between two mountain chains in the northern Andes, which for the past century has been home to large-scale sugar cane plantations in the plains and large herds of cattle on the hillsides. As a result of overplanting sugar cane and cutting down forests to accommodate cattle, the soil has been eroded and the water exhausted, Escobar said.

The solution, he explained, is to design a new model. He is part of a team of academics and activists from many different fields working together to create an ecological, social and economic transition for the Cauca River Valley.

“We don’t know exactly what this new model is, but everyone has to contribute toward imagining a different way of being,” he said.

The endeavor is expected to take the better part of a decade.

“The goal of transition design is to heal the interconnected web of life,” Escobar said. Transition design focuses on a community’s unique needs to find ways to enhance social connections, respect plurality and foster autonomy.

His work in the field is far from complete.

His book on autonomous design theory, Designs for the Pluriverse: Radical Interdependence, Autonomy and the Making of Worlds (Duke University Press), was published just a few months before Escobar retired. He is also an ad hoc professor at the Universidad del Valle and the Universidad de Caldas, both in Colombia, where he continues to teach occasionally and lives for about five months a year.

While he will continue his work in the Cauca River Valley, Escobar also wants to expand beyond academic writing to create a book for lay audiences that explains these ecological design principles. At this point, the only question is whether he will focus on writing primarily in Spanish or English.

By Patty Courtright (B.A. ’75, M.A. ’83)

Published in the Fall 2019 issue | Features

Read More

Mellon funding supports environmental humanities

The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation has awarded a $150,000 two-year…

Summer conference unites Jane Austen fans, scholars

Jane Austen’s works have inspired films and television shows, sequels…

Oral History Fieldwork: #Throwback Photo

Students conduct interviews as part of the folklore curriculum in…