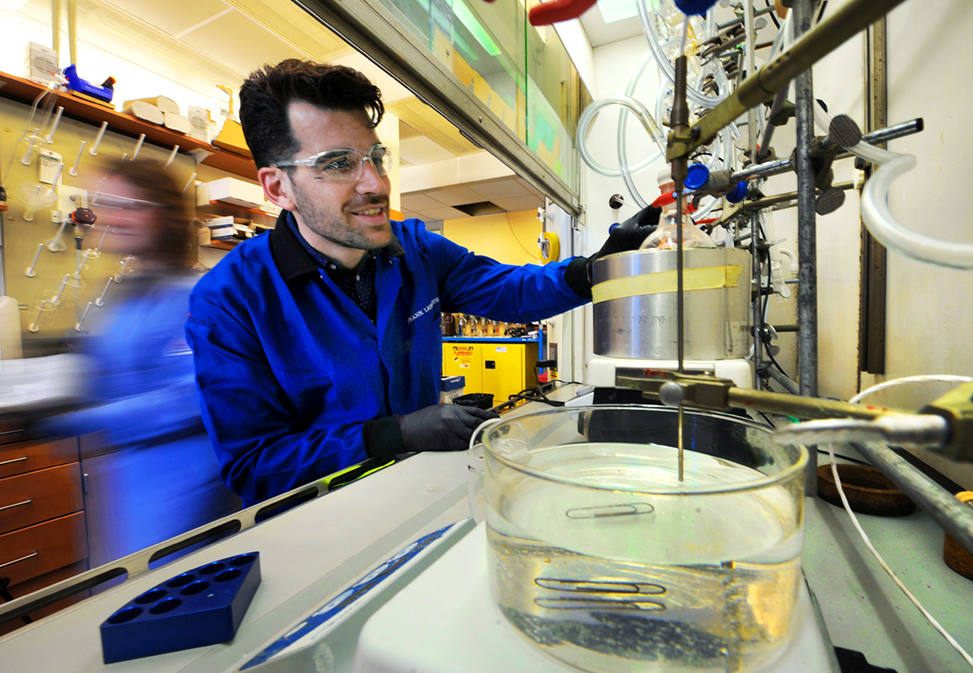

Frank Leibfarth’s research on methods to clean up PFAS contamination is being supported by the UNC Institute for Convergent Science. (photo by Donn Young)

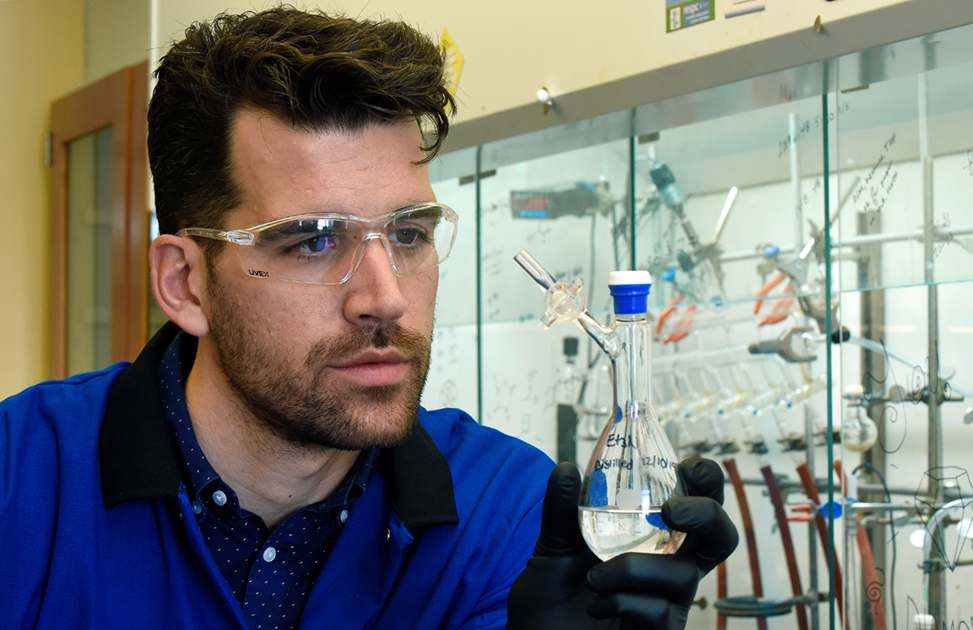

Polymer chemist Frank Leibfarth is rethinking plastics, with a focus on sustainability.

Disposable diapers. That’s what inspired a groundbreaking toxic chemical-capturing resin recently developed by UNC-Chapel Hill assistant professor of chemistry Frank Leibfarth.

After the 2016 discovery that perfluorinated alkylated substances, or PFAS, had contaminated North Carolina’s Cape Fear River Basin, representatives from the state-funded NC Policy Collaboratory visited the College’s chemistry department looking for innovative solutions. Leibfarth’s colleague Marcey Waters suggested hydrogels, the super-swellable resins found in diapers. “Can’t you make a gel that soaks up PFAS?” she asked Leibfarth.

“I went back and read a lot of literature about how diapers work,” said Leibfarth. Hydrogels, it turns out, are made of polymers — substances made from strings of single molecules bonded together. Plastics are polymers. Leibfarth is a polymer chemist, a rising star among a new generation of researchers who believe manmade materials must be both functional and sustainable.

Though well suited to the PFAS challenge, Leibfarth, who joined the UNC faculty in 2016, had never worked on such a laser-focused, rapid-response project. The Leibfarth Group does basic scientific research to create sustainable plastics or develop ways to make existing plastics more sustainable.

“We are not so much problem-driven as we are method-driven,” Leibfarth said. “We’re interested in fundamental creativity.”

Creativity is a big part of Leibfarth’s success. Raised in South Dakota, Leibfarth admits he wasn’t always into science. An athlete — he was a placekicker for the University of South Dakota football team—who learned carpentry skills from his father, Leibfarth fell in love with chemistry as an undergraduate on a summer National Science Foundation fellowship at Columbia University.

“Chemistry is quantitative. You have to have an analytical brain for it, but you also have to have this artistic way of thinking about molecules,” he said. “Chemists are makers. We make things with molecules.”

As a maker of molecules, Leibfarth strives for simplicity.

“There’s a natural drive in science towards complexity,” he said. A polymer chemist might enhance a plastic by tacking on more and more functional groups, the way one creates a Lego structure, adding block after block. But that approach might weaken the structure or increase production costs or reduce sustainability. “We’re finding that we can get high-performing materials from simple building blocks if we focus on understanding how to control their structure and connectivity in previously unforeseen ways,” he said. “That’s the fun part of working at the interface of disciplines.”

One of his lab’s breakthroughs involves developing a sustainable plastic from a common substance by controlling the stereochemistry of polymers in a way that was previously undiscovered. Another involves creating catalysts that make throwaway thermoplastics more economical to upcycle.

With the PFAS work, Leibfarth has entered a new realm — environmental engineering.

The hydrogel suggestion from his chemistry department colleague was all Leibfarth needed. Leibfarth and his team designed a fluorinated resin that, when ground into a powder and added to a water-filtration column, soaks up GenX — the trademarked PFAS made by Chemours at the company’s Fayetteville plant — the way diapers soak up water. GenX is prevalent in the Cape Fear River Basin, which provides drinking water for more than 1.5 million North Carolinians. Because GenX is negatively charged, Leibfarth’s team put positive charges on their resin, creating an extra-sticky electrostatic bond. In tests, Leibfarth’s resin removed more than 80% — or more than four times — the GenX than the best commercial technology.

The work is so promising that the UNC Institute for Convergent Science has partnered with the NC Policy Collaboratory to fund a demonstration phase of the research, with the hope of commercialization.

“It’s highly rewarding,” said Leibfarth, who recently won a Sloan Research Fellowship and a Cottrell Scholar Award, both given to the best-of-the-best among early-career scientists. “We’re much closer to making an impact with the PFAS work than any of the other work we do. That invigorates me and my students.”

Watch a video about Leibfarth’s research.

By Logan Ward

Published in the Spring 2020 issue | Tar Heels Up Close

Read More

Confronting antisemitism

“Topics in Jewish Studies: Confronting Antisemitism” is a new, one-credit-hour…

Good eating and good reading

From Appalachia to Virginia’s Eastern Shore to Southern roadside eats,…