Grand-Mary's cast-iron pan. (photo by Ellen Saunders Duncan '15)

When I was seven, my mother’s beloved grandmother passed away. After a short custody battle, her cast-iron pan came to live with us. It was a complex calculus, deciding who would inherit what. My great-grandparents were never particularly well-off, so the value of their belongings lay in sentiment and memory. You would think that would make those selections and distributions that much easier: different objects would mean more to certain family members. Conversely, it was an arduous process.

At the center of one debate was my great-grandmother’s cast-iron pan. The heavy, gleaming black pan was the centerpiece of the cookware collection and the primary pan for preparing every meal, decade after decade. At breakfast, Grand-Mary regularly fried a dozen eggs and a pound of bacon; at dinner, the pan turned out two or three chickens. My grandfather said she “cooked like a small restaurant.” Between meals, it stood sentry on the back burner of the stove, domiciled there because the pan’s dense weight and service at every meal ruled that the most logical home. Only when company came was the pan removed to the oven’s broiler drawer.

After she cooked each meal, Grand-Mary readied the pan for its next outing. Often this simply meant rubbing the remaining oil back into the surface; other times she used a few splashes of water to clear the pan, set it over low heat to dry and then rub some extra fat into the surface. To inherit this pan would be a coup: its surface held the accumulated flavors, seasoning and residue of no less than two generation’s worth of Grand-Mary’s meals.

Grand-Mary died one hazy, warm evening in September. After the funeral, standing in her kitchen, I saw Grand-Mary’s home as I had never seen it: the intimate, personal world she had curated and cultivated over the space of decades was being divided up.

Ultimately, the fate of the cast-iron pan came down to my mother and her aunt. My mother won out for two reasons: she would continue using the pan, and she’s a Saunders woman by blood. My mother was not only the first grandchild, but the first girl born into the Saunders family in decades.

One evening my father burned the pan.

Burning a cast-iron pan ruins the seasoned surface that develops through frequent use and careful cultivation. That surface must be removed — char, seasoning, fat, and all — with sandpaper or an abrasive scrub. Then you begin anew with developing the seasoning, transforming the cold, porous iron to a lustrous, warm surface that imparts complex flavors and is naturally non-stick. It’s this surface that attracts cooks to cast-iron, meal after meal.

A cast-iron pan is a punishing instrument: utilitarian and durable until treated improperly, then requiring a ponderous, delicate routine to render it useful and usable — its gleaming, smooth beautiful black surface deceptively hot to the touch.

When my father burned that pan, it required my mother to remove the accrued seasoning, flavor, care and expertise her grandmother had imparted over the course of decades of use.

My mother’s reaction was banishment: either my father or the cast-iron pan. Like many great Southern family stories, this one ended with something pushed to the back of the closet: the cast-iron pan exiled to a dark pantry corner for several years. In our cooking educations, my sister and I did learn how to cook on cast-iron, but with a far less valuable pan, purchased at a thrift store. Once we proved ourselves capable of following cast-iron’s etiquette, Grand-Mary’s pan made a quiet, triumphant return.

Since its resurrection, the pan has cooked many of the old standbys — pancakes, cornbread, bacon, chicken pot pie — and a few meals Grand-Mary never would have considered. One day, I will inherit that pan from my mother, vowing to respect its memories through use. While some Southern families inherit silver and china, mine treasures that enduring cast-iron pan.

[ Essay by Ellen Saunders Duncan ’15, a junior majoring in interdisciplinary studies and minoring in entrepreneurship. A longer version of this essay can be found at southernthings.web.unc.edu. The website was created in a class taught by American studies professor Bernie Herman.]

Published in the Fall 2013 issue | Finale

Read More

Exploring shamans and rock art in South Africa

UNC anthropologist Silvia Tomášková spent 2010 to 2011 in South…

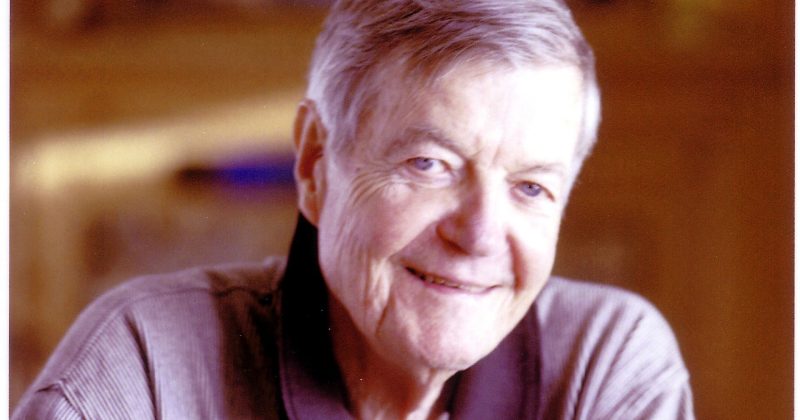

Frank Borden Hanes Sr. leaves lasting legacy

Frank Borden Hanes Sr., a native of Winston-Salem, N.C., and…

Rod Brooks tackles a global crisis, one meal at a time

UNC alumnus Rod Brooks ’89 is working to end world…